Character and World-Building

Adding Depth While Staying Concise

While conciseness is key in scriptwriting, creating rich, believable characters and worlds is crucial for engaging stories. This guide explores how to:

- Develop these elements thoroughly

- Reveal them efficiently in your script

- Balance comprehensive development with production realities

Let's dive in!

Building Characters

Strong characters are essential to any compelling script. They drive the story and engage the audience. This section covers techniques for developing effective characters, including:

- Character outline techniques

- An actor's approach to character development

- Building characters from theme

- Discovering character through the writing process

As we proceed, remember, while thorough development is important, characters often evolve during production. Create a solid foundation, but stay flexible.

Character Exploration

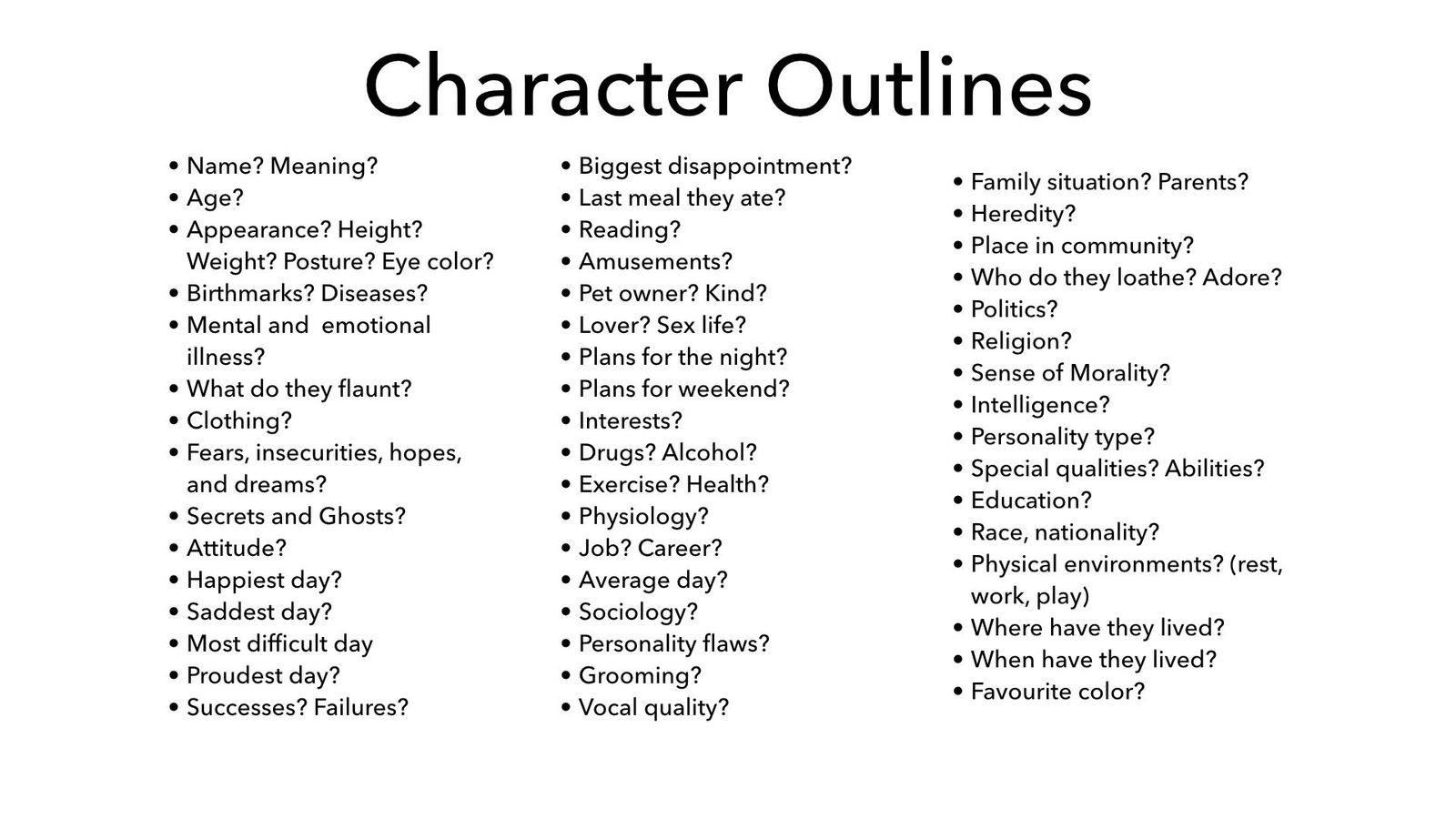

Character outline lists

Writers are often encouraged to use outline lists, which explore multiple facets of your character’s traits.

You can take this as far as you want, focusing on the physical characteristics and small details, such as what they have in their purse, wallet, or pockets. This exercise is one where you can go to the furthest extremes.

Mind Maps

Use mind maps to visually explore character connections and traits. Start with your character's name in the center and branch out with key aspects like personality, relationships, goals, and fears.

Timelines

Creating character timelines can be particularly helpful, especially when writing longer works like a series. They serve multiple purposes:

- Track the character's personal history and development

- Identify and prevent plot holes

- Contextualize the character within broader historical events

For example, a timeline can help you understand how growing up in the 1960s versus the 2000s would shape your character's worldview, experiences, and reactions. This method ensures your character's background and actions remain consistent and believable throughout your script.

Scrapbooks

Compile a character scrapbook with images, quotes, or objects that represent your character. This visual and tactile method can inspire new ideas and deepen your understanding of the character's world.

An Actor’s Approach

One handy technique for writers is adopting an actor's character analysis approach. This method can help you dive deep into your character's psyche and motivations, creating more rounded and believable personalities.

Actors often break down a script and search for details that answer specific questions about their characters. As a writer, you can use this same approach to develop your characters more fully:

- Character Core:

- Spine: What does the character want within their life? How does this drive them through the story?

- Obstacles/Issues: What keeps them from their wants? What flaws hold them back?

- Action Verbs: How specifically does your character pursue what they want?

- Background

- History/Backstory: What past events shaped them into who they are?

- What just happened: What occurred moments before they entered the story?

- Relationships

- What relationships does your character have? Consider:

- Mentors or allies

- Sidekicks

- Love interests

- Family (parent, child, sibling, etc.)

- Evil mentors

- Henchmen

- Tempters/temptresses

- What relationships does your character have? Consider:

- Worldview

- Beliefs: What do they believe in? How do they perceive the world?

- Ghosts & Secrets: What haunts your character? What secrets do they hold?

- Characteristics

- Skills & Traits: Consider physical, mental, or emotional attributes

- Habits: Both positive and negative

- Images/objects: What physical elements or objects hold meaning for them?

This approach looks at the characters from an empathetic point of view. This is particularly valuable when writing villains or antagonists. The best actors never approach these roles negatively. Instead, they find justification for their character's actions. What higher goals are they pursuing? What makes their actions necessary or even righteous in their mind?

Building from theme

As discussed previously, the theme can be built out of character or plot, so it’s not hard to reverse engineer this and make the character from the theme.

Once you have your premise, you’ll likely have a sense of your protagonist and the antagonist that stands in the way of them achieving their goal. From here, you can work on their opposing worldviews that builds out the underlying thesis of the story.

Once you have that, ask yourself what are the different viewpoints and groups that develop from these three sides:

- Those who agree with the thesis statement.

- Those who disagree with the thesis statement.

- Those who are indifferent to the thesis statement.

Then start exploring relationships like the ones above—mentor/allies, sidekicks, love interests, family, evil mentors, henchmen, and tempters—and add more characters if needed.

The theme can also reflect what a character wants or represent their weaknesses or flawed perceptions of the world. These are the obstacles a character must overcome to achieve what they want in life.

Consider where these flawed beliefs come from. Was it a part of their backstory? Their environment? From the events of the story? All of these are statements about your theme.

Similarly, what motivates them to change? What is their want? Where does it come from? Again, what is their backstory, their environment, or the events of the story?

Lastly, consider symbols, imagery, and thematic elements that can shape a character's dialogue, appearance, or quirks:

- their mood

- their objects (jewelry, weapons, creatures)

- anecdotes and stories of their past

- phrases and vocabulary

- quirks and traits

- names

These can represent the story's themes and the characters' fatal flaws, wants, and motivations.

Discovering Through Writing

Our choices build the character before we begin writing or along the way. It is often easier to consider these details while creating and rewriting the story. This process of discovery through writing can reveal nuances and depths to your characters that you might not have anticipated during initial planning.

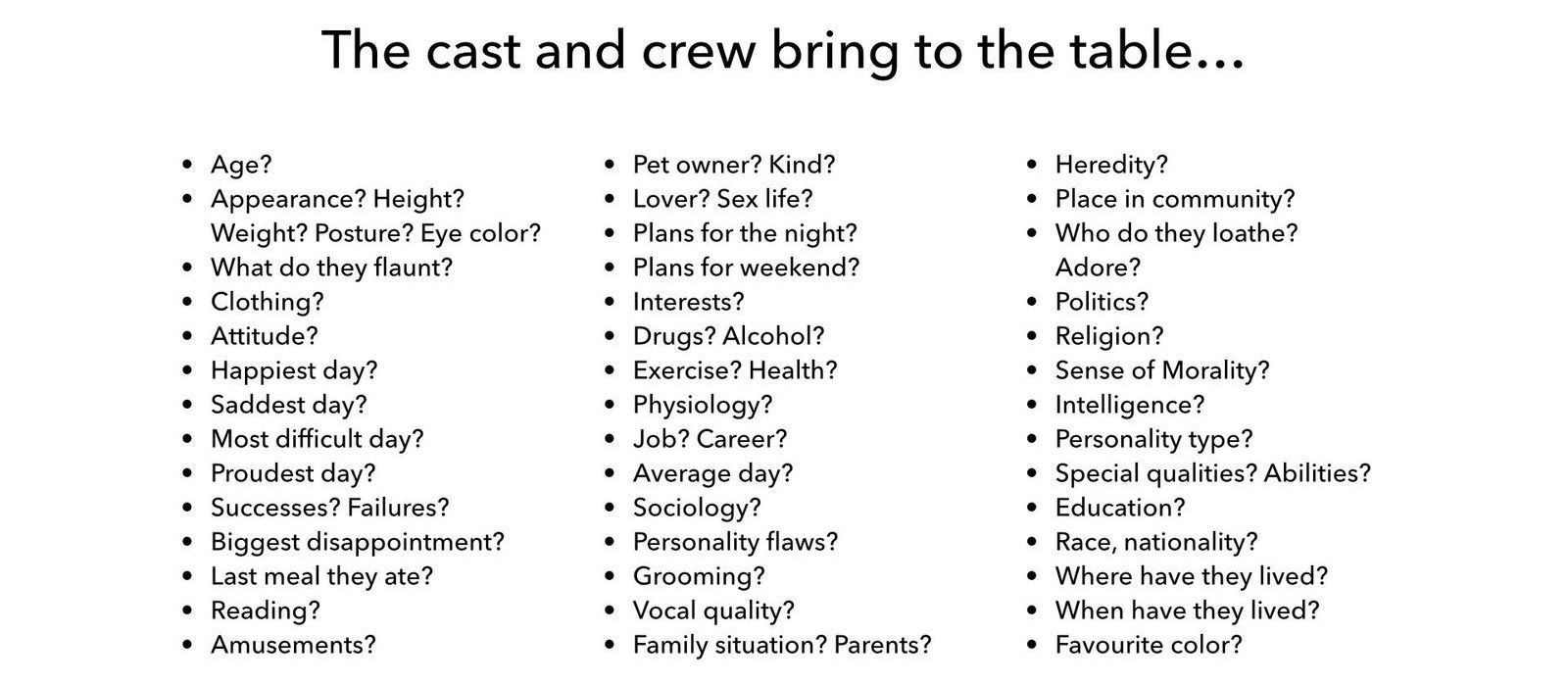

The Reality of Production for Characters

While detailed character exploration is valuable, it's crucial to remember that your cast and crew will inevitably bring their own interpretations and ideas to the table. This can lead to significant changes in how your characters are portrayed and developed.

For instance:

- Actors will craft their own path through a scene or story, often bringing nuances you hadn't considered.

- An actor might request changes to set dressing, costumes, or props to better align with their understanding of the character. I've seen production put on hold because an actor didn't like the set dressing in a store window and they needed to redress it with things she felt her character would be interested in.

- Directors may have different visions for character interactions or development.

- When faced with budget or time constraints, producers might work to compress multiple characters into one, significantly altering character dynamics and arcs.

We can do all the work in the world to develop our characters, but whatever the cast and crew bring will change that vision. This isn't necessarily a bad thing - it's often where the magic of collaborative storytelling happens. However, it's important to be prepared for these changes and to approach character development with a degree of flexibility.

Crafting Characters into Our Scripts

Using WOARO

WOARO can reveal many aspects of a character:

- What does your character want (internal and external)?

- What obstacles stand in their way (internal and external)?

- What actions do they take, and how do they respond?

- What is the outcome?

- How are they described?

These questions can help shape your character—right from the first page of your script (and if you take internal wants and obstacles into account long before).

Placing your characters in action forces you (and them) to make choices about who they are. Whether you outline beforehand or work on it the day of writing, it is ALWAYS about making choices.

Note: The concepts and questions presented here build upon our earlier discussions of Want, Obstacle, Outcome, and Action and Response. For a more comprehensive understanding of how these elements interact to create compelling characters and drive your story forward, you may find it helpful to revisit these pages:

These pages provide foundational insights that complement and enhance the character-building techniques discussed here.

Want and Obstacles

Above all else, a character is defined by their internal and external wants.

The outer goals drive the story but characters are also driven by their inner desires that extend over a lifetime. These are life's big goals and are defined by your character's history.

Similarly, external and inner obstacles shape a character's journey, standing in the way of what they want and holding them back.

Also, a character's wants and obstacles define their allies, friends, and enemies.

Want and obstacles are the bedrock of your character and story. If the choices you make here shift, then it fundamentally affects both. The sooner you commit to this choice, the easier your writing will become.

Action and Response

It's important to remember that a character's actions or responses (what they do, say, or don't do or say) define them. They reflect the engrained behaviours built upon years of experience and history.

Action is always done with the intention to confront change—either to stop it from happening or to create it. It can be done involuntarily or by choice—both options define your character.

Remember that not everything that defines a character is a choice. Some things are inherently a part of a character's wants, drives, and obstacles.

Also, remember that actions depend on specificity. Knowing exactly how your character loves, hates, defends, and responds defines them.

This specificity will also include the words a character uses. Are they eloquent, crass, or pandering? Do they talk down to some people but not others? How do they use their words?

Similarly, how does your character respond? Whether a character responds immediately to stimuli or thinks about it beforehand and how they respond all indicate their personality.

Action and response are also significant indicators of emotion—even if we can't show it in the script. If a character fights back or runs away, it tells us something about their emotional response. If they don't react, it also tells us something.

Lastly, if the field of your character's actions or responses changes, it represents character change. For example, a character who shifts from love for another character into hate.

Applying WOARO at Every Level

Remember to apply WOARO at every level of your story—scene, sequence, act, story, and series. Each of these moments is an opportunity to reveal character, show them struggling, and demonstrate how they fail, grow, or adapt.

As you write, consider these questions:

Want:

- Who wants what?

- Where is the want on the page? Can it be stronger? Can it appear earlier?

Obstacle:

- Where is the obstacle? Where does it appear?

- Can it be introduced earlier? Can it be stronger? Can it be impossible to ignore?

Action:

- What's the action? Where is it? How is it expressed (action, dialogue, or both)?

- Can it appear earlier? Can it be more assertive or direct against the obstacle and towards the want?

- Is the action voluntary or involuntary? How does this choice define the character?

- How specific is the action? Does it clearly show how the character loves, hates, defends, or responds?

Response:

- What's the character or world's response to the action?

- How does it affect the direction of the story?

- Does the character respond immediately or after consideration? What does this reveal about their personality?

- What does the response (or lack thereof) indicate about the character's emotional state?

- Has the character's field of responses changed? Does this represent character growth or change?

Outcome:

- What is the outcome?

- Do you show it?

- Does the character get what they want? Why does it happen? If they don't get it, why not?

By continually revisiting these questions at each level, you ensure that every WOARO cycle not only drives your story forward but also reveals more about your characters. This layered approach creates depth and complexity, allowing your characters to evolve naturally throughout the narrative.

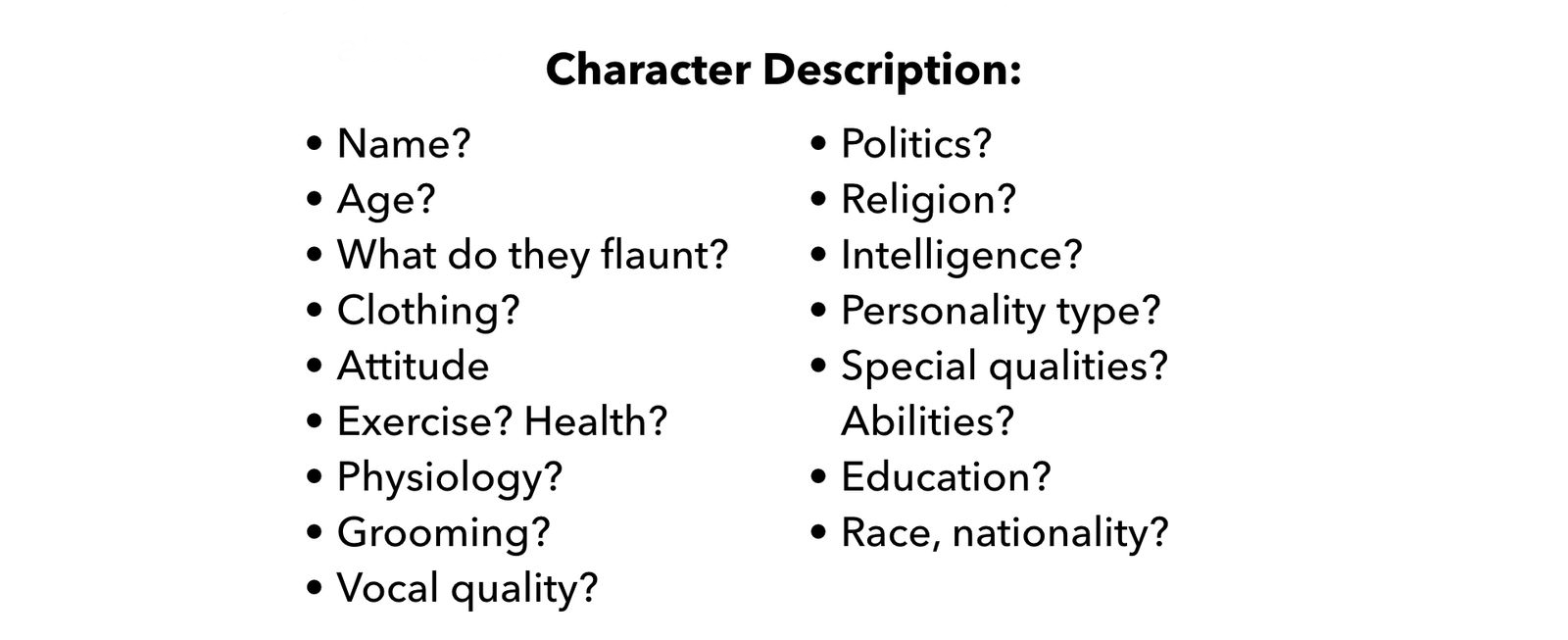

Character descriptions

Remember, character descriptions are more about their essence and less about physical traits or backstory.

What do we need to know about characters when they first appear physically in your story?

Notice what we can hint at just through that description.

Although we listed many details above, this doesn’t mean you should include them all in your description.

World Building

World-building, like character-building, is essential for immersive storytelling, but it should always serve your narrative. Remember: build your world through your story, not vice versa. The goal is to create a clear, immersive experience without pulling readers out of the narrative.

As with characters, it's important to remember the realities of production when world-building. Just as character details may change, aspects of your world may be altered or discarded during the filmmaking process.

Discovering Your World

World List

Similar to the character list, we can consider different aspects of our world to build it out:

- Place and Architecture - What is the geography and climate of this place? What resources do they have? How does the architecture of the place relate to it?

- Life - What does a typical day look like for the people in your world? If there is a class system, what is it, and how do the citizens interact daily?

- Language - How do they communicate? (Of course, be cautious with this since creating a language that is too complex may hinder the storytelling.)

- Art and Culture - Is art present in this world? What sort of art? How do the intellectuals and the masses view it?

- History - What are the key, relevant events that led to the beginning of your story? What has built it up? What has hampered it?

- Science & Technology - What role has technology played in the development of this society? What has been discovered? What hasn’t?

- Law - What system of rules exist? How is it enforced? Is it working?

As you explore these details, ask yourself how they connect. How has history impacted art and culture? How has science and technology impacted architecture and vice versa?

Building from themes

Again, consider what symbols and thematic elements can be adopted into your world:

- objects

- iconography

- vocabulary

- names

- specific locations and places

- weather

Not only does every place carry meaning within a world's history and culture, but also about every character.

Develop a Set of Rules

A helpful idea is to develop a tight and precise set of your world's most important rules. Some can be broken, and some cannot. For example, social rules can be broken, but gravity can't.

Some rules to consider:

- rules of magic or rules of science

- rules of the hierarchy and the roles within it

- rules of the natural world

- rules of individual characters

What happens if you break some rules? What are the consequences? How do the rules create limitations and edges in your world?

Discover World Details in the Process of Writing

Our choices build the story and the world before we begin writing or along the way. It is often easier to consider these details while creating and rewriting the story so that we don't waste too much energy and time on work that gets lost in the filmmaking process. This process of discovery can reveal interesting connections and aspects of your world that you might not have planned initially.

Additional World-Building Techniques:

Many techniques used for character development can also be powerful tools for world-building:

- Mind Maps: Use these to explore connections between different elements of your world, such as cultures, locations, or historical events.

- Timelines: Create a chronology of your world's history, helping you track important events and understand how they shape the current state of your fictional universe.

- Scrapbooks: Compile visual inspirations for your world's aesthetics, architecture, costumes, and atmosphere.

- Outline Lists: Similar to character trait lists, create detailed lists of world elements like flora, fauna, technologies, or magical systems.

These methods can help you develop a rich, consistent world while also ensuring it aligns with and enhances your character development and overall narrative.

The Reality of Production for World-Building

Similar to character-building, the intricate world you've built on paper may face significant alterations during the production process. The danger of excessive world-building is that it often doesn't make it to the page or screen, or the cast and crew may discard or modify elements.

Consider these real-world production scenarios:

- Budget constraints might force the compression of multiple locations into one, requiring you to rethink how your world is presented.

- Time limitations could lead to cutting scenes that showcase particular aspects of your world.

- Producers might decide to move scenes from one carefully crafted location to an already established one for practical reasons.

- Production designers and art directors will bring their own vision to your world, which may differ from what you initially imagined.

Remember: while it's important to build your world through your story, the realities of production may require you to adapt that world significantly. The goal is to create a clear, immersive experience without pulling readers out of the narrative, but also to be prepared for the inevitable changes that come with bringing a script to life.

We can craft everything perfectly in our scripts, but they may not survive the realities of production intact. This emphasizes the importance of focusing on the core elements of your world that are crucial to the story, while being flexible about the details that might change.

Placing world-building into your script

When integrating your world-building into your script, remember the golden rule: show, don't tell. Your goal is to reveal your world organically through the story, rather than explaining it outright.

Opening Descriptions

Use the opening descriptions of places to show elements of the world. Keep them tight, allowing only a maximum of 3-4 lines for each. Fewer words are often better.

Integrate with WOARO

- Wants can show what is valuable in this world.

- Obstacles can reveal conflicts between groups and societal structures—or dangerous creatures or spaces.

- Actions and responses can highlight characters' language, tools, rules, and everyday existence.

Show the Rules in Action

Instead of explaining your world's rules, show them through character actions and consequences. Let the audience discover the rules alongside your characters.

Use Visual Elements

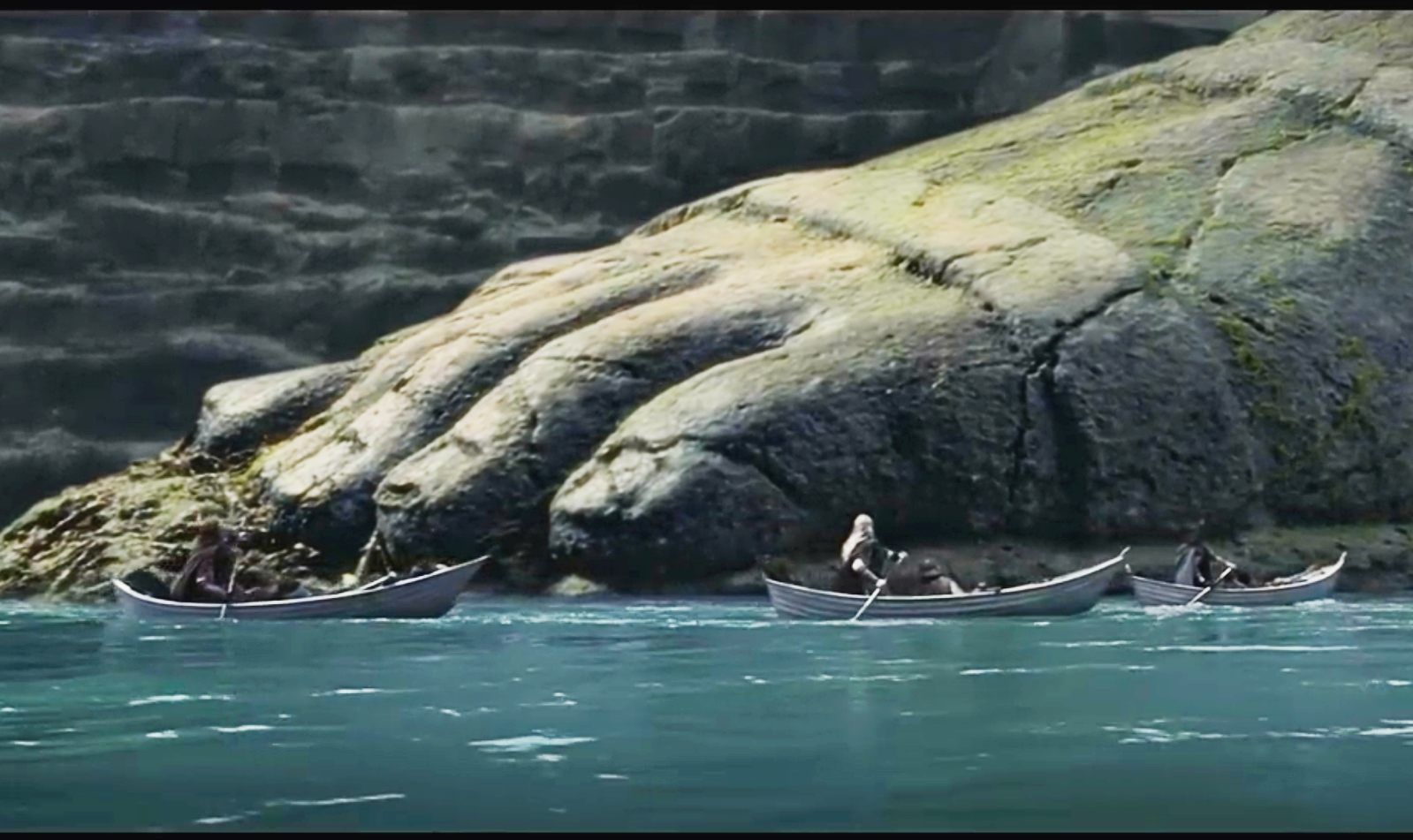

Consider how visual elements can convey information about your world:

- In "The Lord of the Rings," large statues across the landscape communicate a deep history without explicit explanation.

Statues in the Lord of the Rings

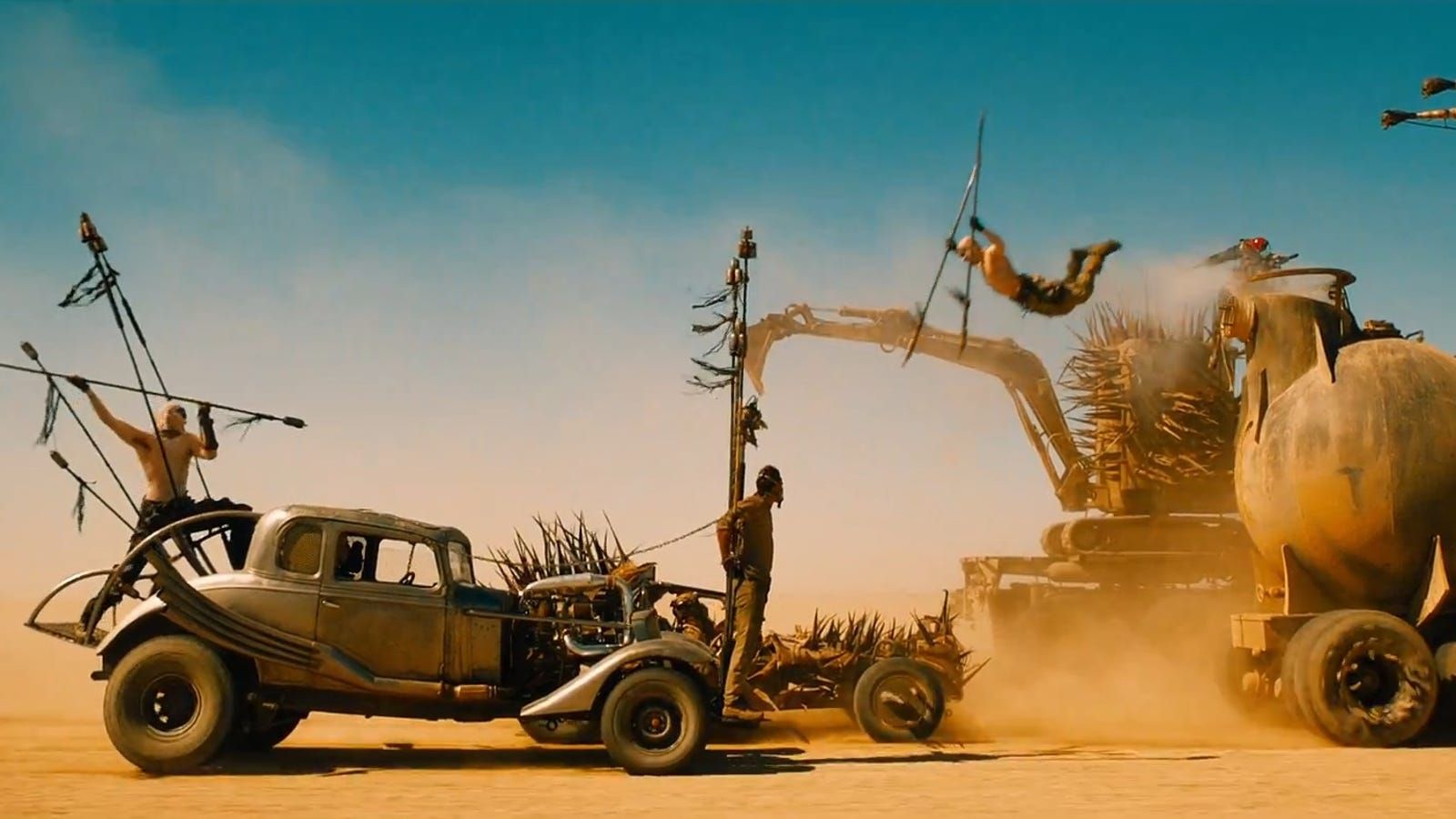

- "Mad Max: Fury Road" reveals its post-apocalyptic world through costumes, vehicles, and character behaviours, maintaining its pace without pausing for exposition.

Mad Max: Fury Road

Character Interactions

Every character interaction is an opportunity to reveal information about your world. Dialog, behavior, and reactions can all subtly convey world details.

Remember, the key is to create a clear, immersive experience without pulling readers out of the narrative. By focusing on what serves your story and revealing world details organically, you'll create a rich, believable world that enhances rather than overshadows your narrative.

Conclusion

Let's recap the crucial takeaways of character and world-building:

- Thorough Exploration: Use various techniques to develop a deep understanding of your characters and their world.

- Selective Application: Not every detail needs to make it to the page. Choose what best serves your story.

- Show, Don't Tell: Reveal character and world details through action, dialogue, and visual elements rather than exposition.

- Use WOARO: This technique helps you organically integrate character and world details into your script.

- Flexibility is Key: Be prepared for the collaborative nature of filmmaking. Your detailed work provides a solid foundation, but remain open to changes.

By balancing thorough development with selective application, you'll create rich stories that can adapt to production realities while retaining their essence.