Film 210: Week 10

Larger Story Forms

In this lesson, you’ll learn:

- Different structural approaches are available to organize your stories

- How story structure evolved from classical to modern frameworks

- The variety of ways successful films and shows are organized

- How to choose structural approaches that serve your story’s purpose

- How WOARO works within any structural framework you select

Let’s begin!

Why Study Different Structural Approaches

You’ve explored WOARO - the fundamental building blocks of storytelling. Now it’s time to explore how these elements can be organized into larger story frameworks.

Think of story structure like the frame of a bridge. You can build a suspension bridge, an arch bridge, or a beam bridge - each uses different engineering principles and works better for various situations. But whatever design you choose, you need solid construction or the whole thing collapses.

Different structural approaches are like different architectural blueprints. Understanding your options helps you make intentional choices about organizing your story.

Classical Foundations

Aristotle’s Poetics

Aristotle essentially invented dramatic theory in the West. He was the first to analyze what makes stories work systematically, establishing foundational principles that still influence storytelling today:

- The plot must be complete and have unity of action

- Simple plots create change without reversal or recognition

- Complex plots include reversal, recognition, or both (which turn upon surprise)

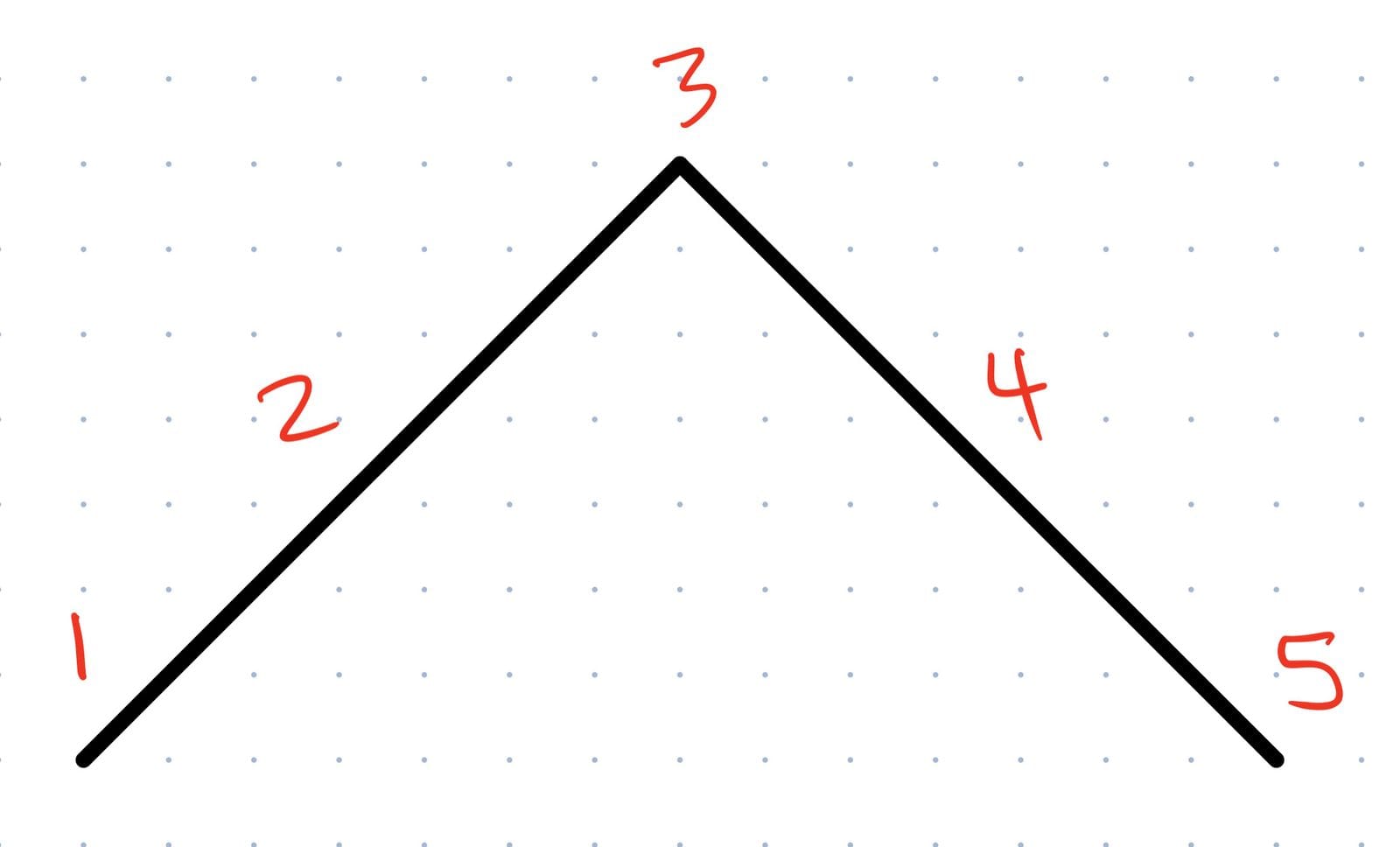

Freytag’s Pyramid (1863)

The German playwright Gustav Freytag wrote Die Technik des Dramas, mapping the 5-act dramatic structure into what became known as Freytag’s pyramid:

- Exposition (initially called introduction)

- Rising action (rise)

- Climax

- Falling action (return or fall)

- Catastrophe, denouement, resolution, or revelation

Modern Screenplay Structure

Syd Field’s Screenplay Structure (1979)

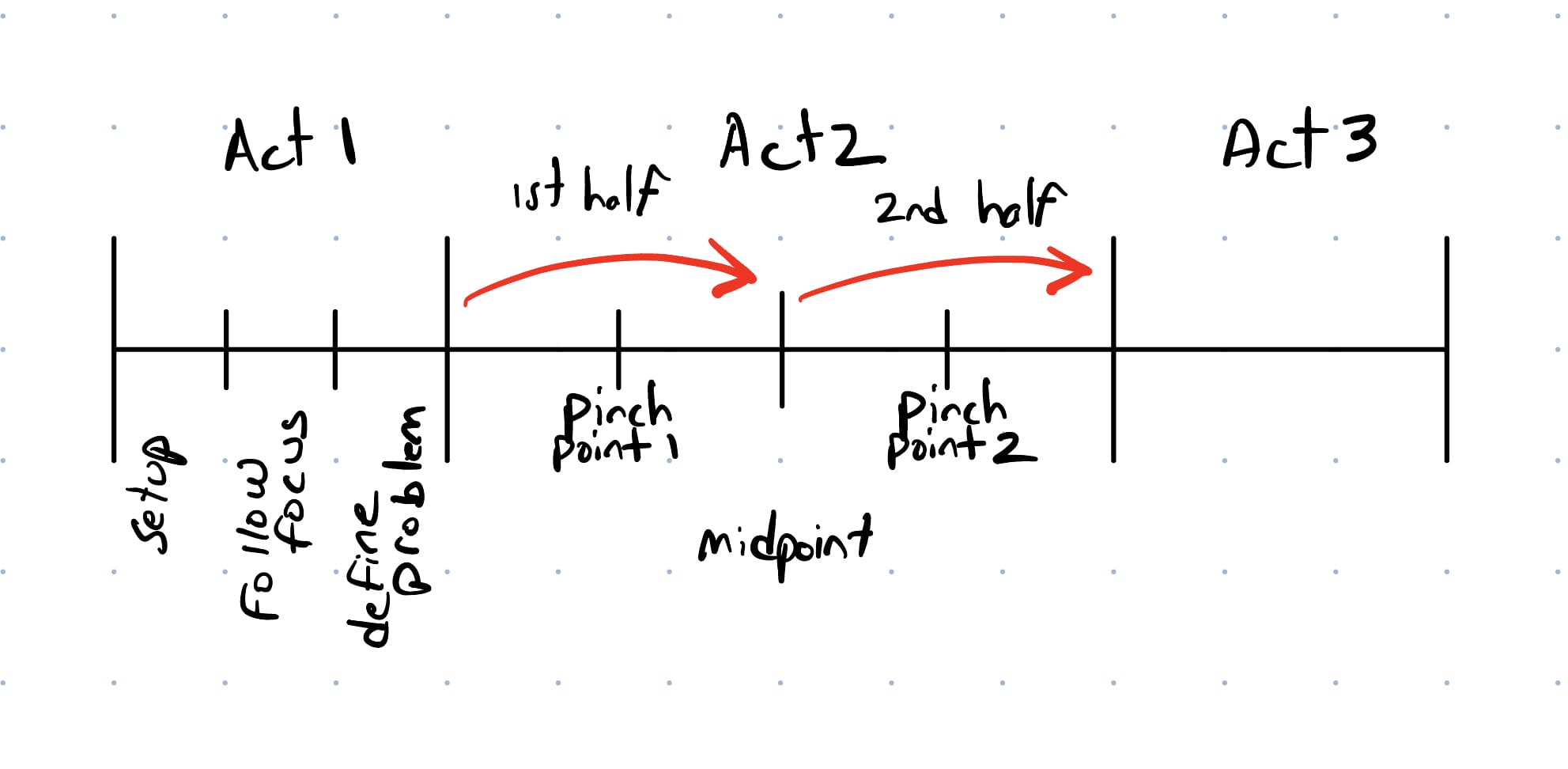

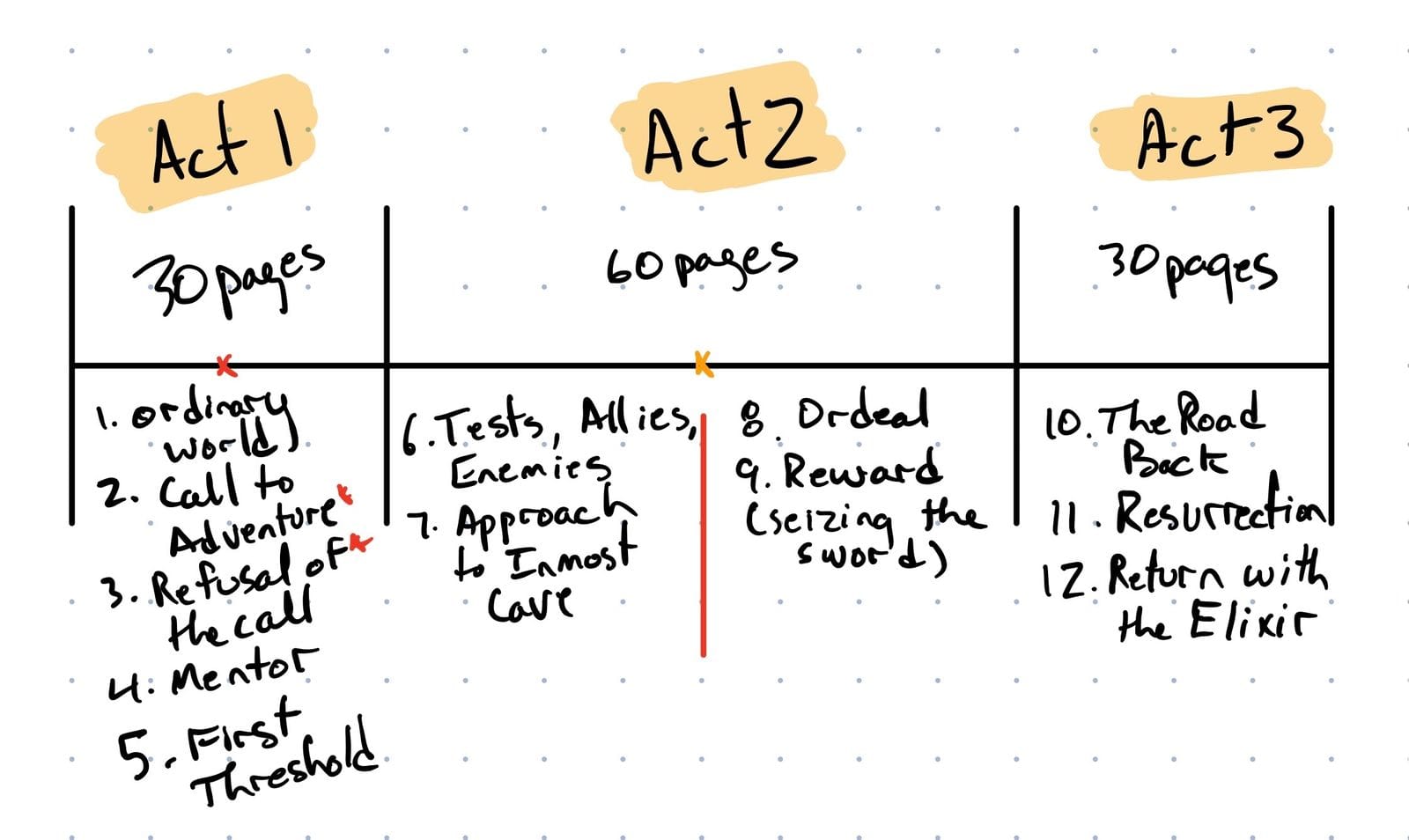

Field’s book Screenplay revolutionized how writers approach film structure by making the abstract concept of “three acts” practical and specific.

Field’s key innovation: Breaking structure into manageable, functional units:

- Three-act framework (30/60/30 pages) with plot points at key moments

- Act 1 is subdivided into three 10-page sections, each with a clear purpose

- Act 2 is split in half by the midpoint - a crucial moment that “guides you and keeps you on course”

- Pinch points added to maintain story momentum

Field showed writers exactly what should happen when, transforming large structural challenges into smaller, achievable pieces. This practical approach influenced virtually all subsequent screenplay structure thinking.

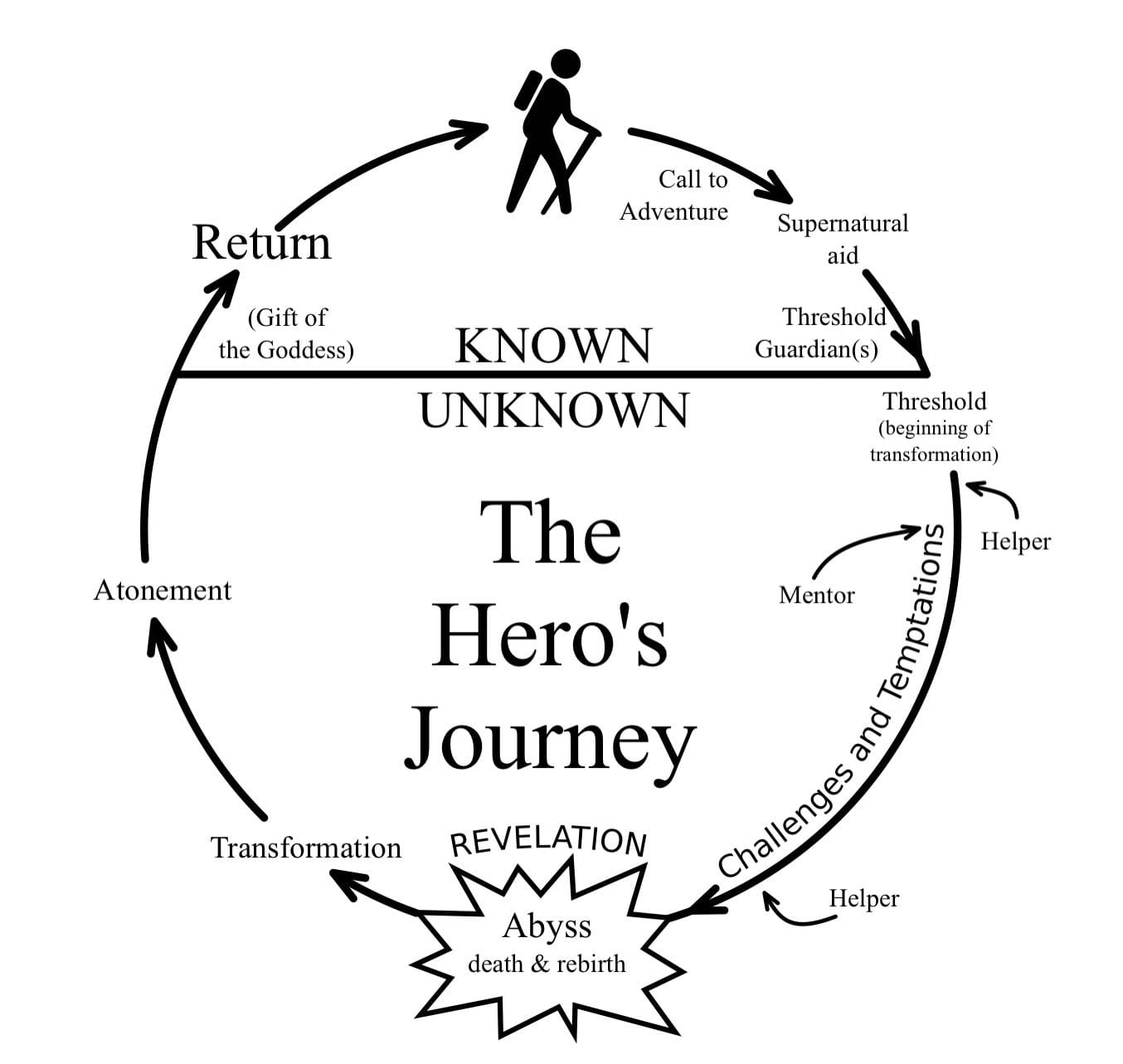

Christopher Vogler’s Writer’s Journey (1998)

Vogler’s innovation was adapting Joseph Campbell’s mythological research into practical storytelling language. He took the abstract concept of the “monomyth” and gave writers specific, usable terminology.

Vogler’s key contributions:

- Circular structure emphasizing character transformation - the hero returns changed

- Clear terminology for story stages: Ordinary World, Call to Adventure, Crossing the Threshold, Mentors, Tests and Allies, The Road Back

- Two-world framework - Ordinary World vs. Special World, making the journey structure concrete

- Universal applicability - showing how mythic patterns work across genres and stories

Vogler gave writers a vocabulary to discuss character arcs and story progression that transcended specific genres, making the Hero’s Journey accessible to modern screenwriters.

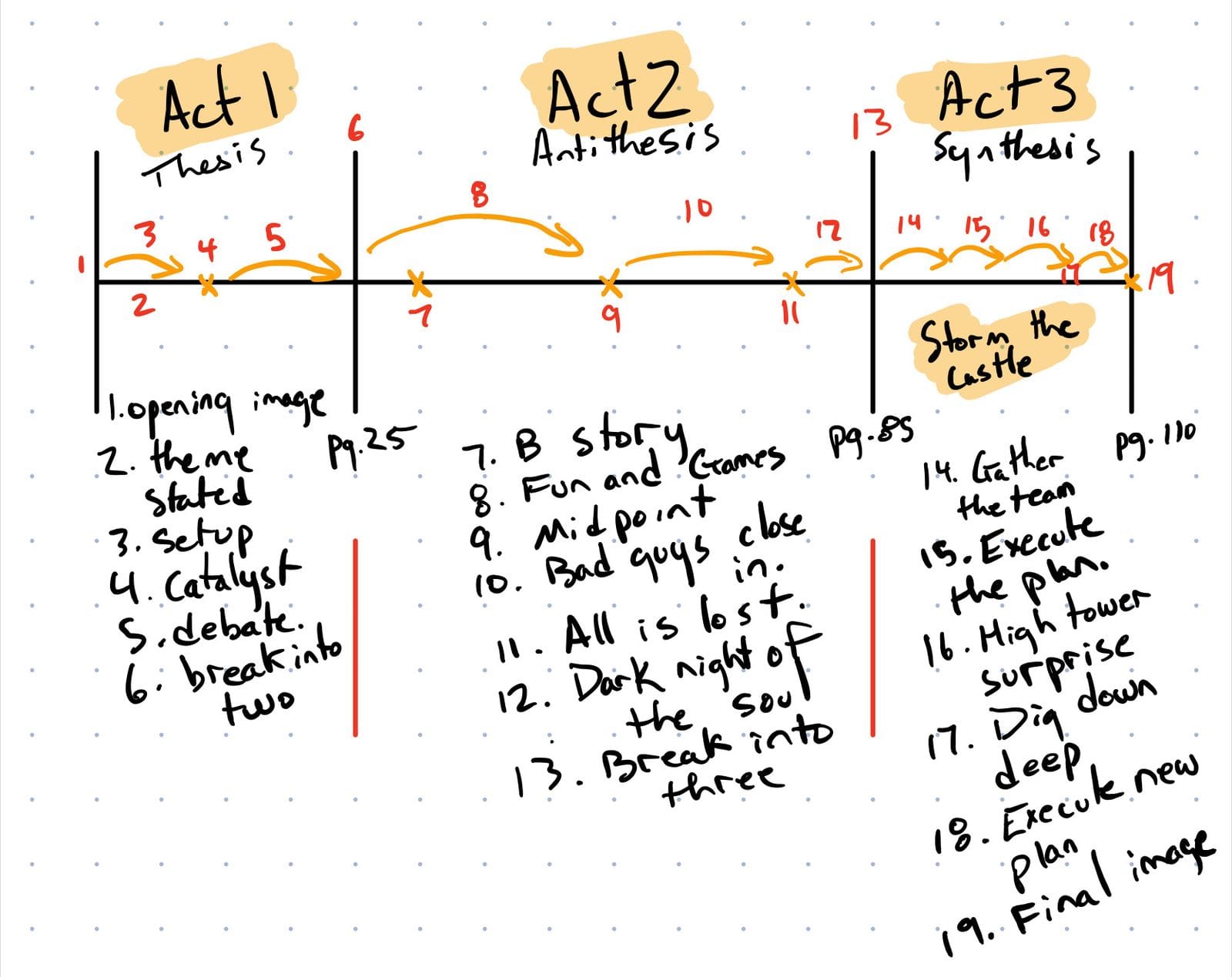

Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat (2005)

Building on Syd Field’s framework and other clarifications, Snyder created the industry standard vocabulary for discussing screenplay structure.

Save the Cat’s innovations:

- Detailed beat language - 19 specific beats with memorable names like “Fun and Games,” “All is Lost,” and “Dark Night of the Soul”

- Industry communication tool - gave producers and writers a common vocabulary to discuss story problems in development meetings

- Filled structural gaps - provided specific guidance for areas that Field and Vogler left vague (like “what exactly happens in pages 30-55?”)

- Practical specificity - answered the question “what should be happening on this exact page?”

Snyder’s impact made the discussion of story structure more precise and accessible across the industry. Terms like “Fun and Games” and “All is Lost” became shorthand in Hollywood development meetings, creating a common language that bridged the gap between writers and producers.

Television and Episodic Structures

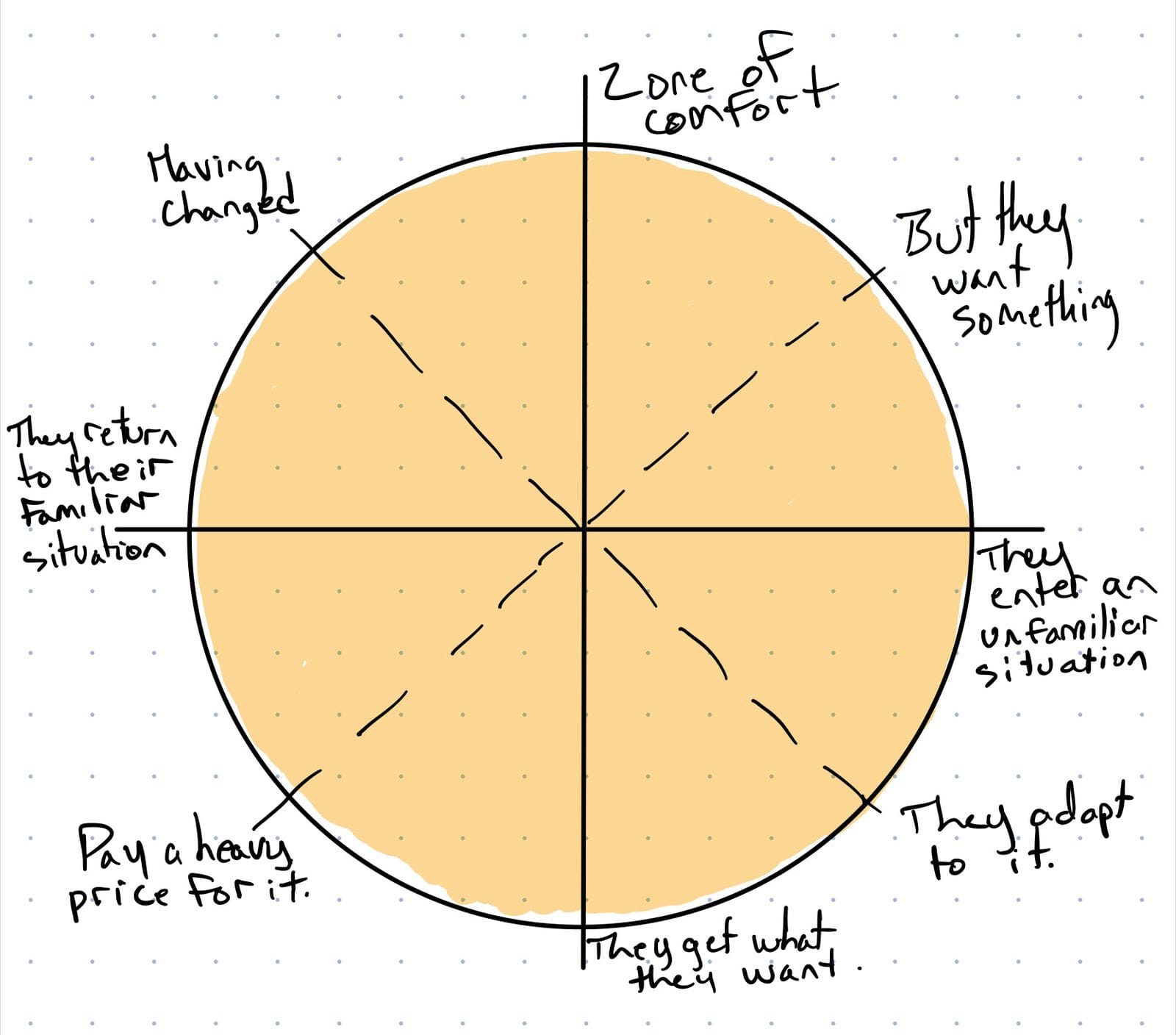

Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

Dan Harmon took Vogler’s Hero’s Journey and simplified it into eight beats for episodic television, demonstrating how mythic structure adapts to different storytelling needs.

This circular structure works perfectly for shows that need to reset while showing character growth episode by episode.

The Harold

From improv and used in shows like Modern Family. Although much of it is word-of-mouth, the Improv Wiki describes it as being constructed as an introduction that leads to separate scenes, back to a group scene, then repeat the separate/group scene cycle:

- Opening

- Scenes A1, B1, C1

- Group Game

- Scenes A2, B2, C2

- Group Game

- Scenes A3, B3, C3

Traditional Broadcast Structure

A half-hour sitcom is about 40-50 pages (not the 1:1 ratio of feature films). Drama series are around 60 pages (unless they are faster-paced, which leads to 70).

Structure includes:

- Teaser - The brief one-minute or so cold open of a show

- The acts - Sitcoms usually have two or three acts. Dramas have four or five acts (or six acts in the case of ABC). This adds up to around eight pages per act or 15 minutes, including the commercials (or 10 pages/minutes per act if six acts long)

- Tag - The epilogue - About a minute that ties up the loose ends

Due to the structure, you build around springboards and cliffhangers, which propel the conflict forward and then hook you into returning after the commercial break.

Example structure:

- Teaser - The character is called to find a solution to a problem

- Act One - First steps towards that solution

- End of Act One - A problem occurs that thwarts the solution

- Act Two - The character deals with the new problem while pursuing their original focus

- Act Three - The real problem reveals itself

- Act Three break - The character is in serious trouble (stakes are raised)

- Act Four - Resolution and solving the problem

Streaming Liberation

The moment you lose commercials, the rules begin to change. Cable, Prime, and Netflix all rely on formats that do not fit the traditional constraints. Without commercial breaks, you can return to classical filmmaking structures and experiment with unique forms that don’t need to break every 8-15 minutes. This opens up creative possibilities for interesting and unique structural forms. And on larger shows, with multiple storylines, they are stacked.

Alternative Approaches

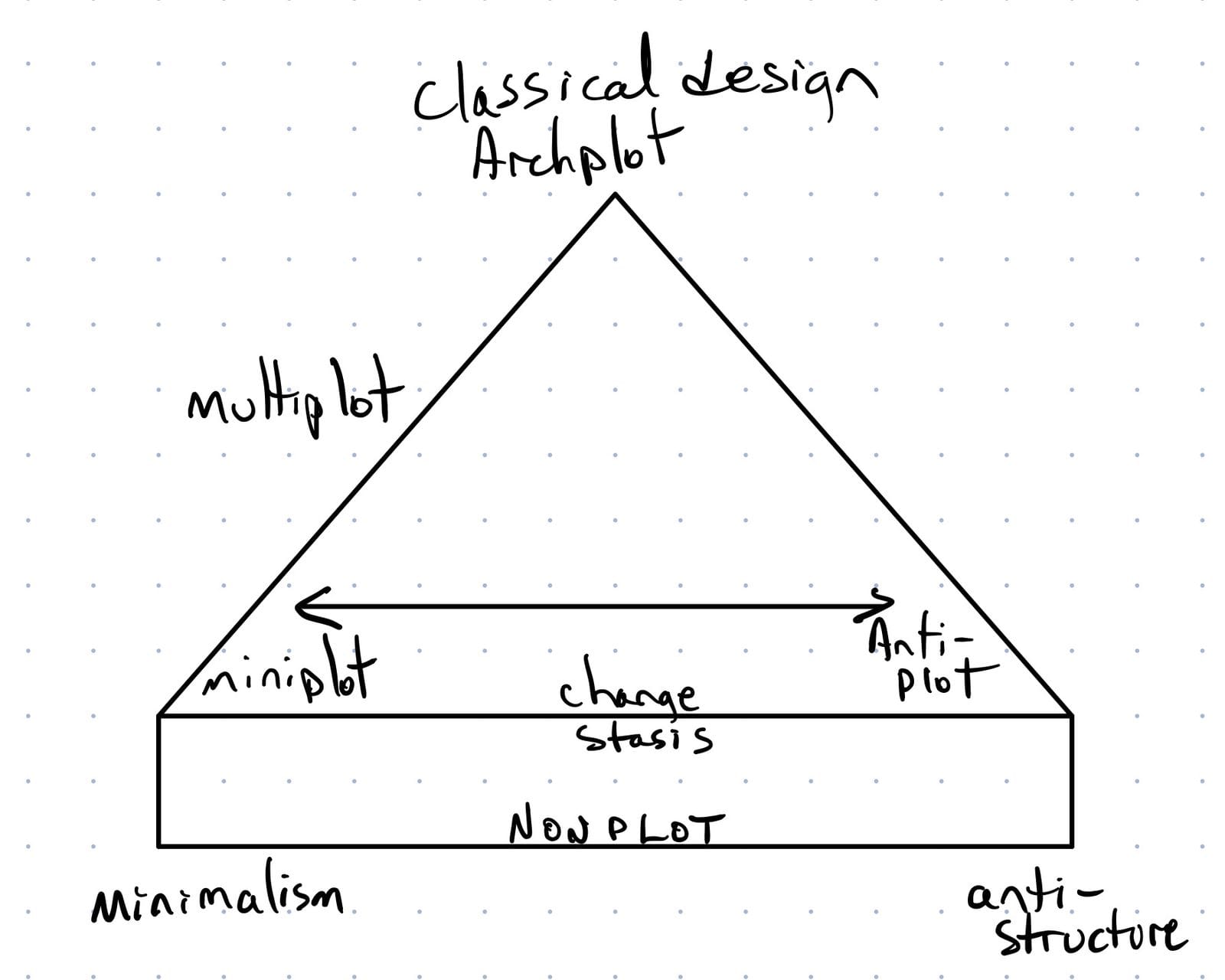

Robert McKee's Story Spectrum

McKee identified three fundamental approaches to story structure, forming a triangle of possibilities:

Classical Design (Archplot):

- Causality, closed ending, linear time, external conflict, single protagonist, consistent reality, active protagonist

Minimalism (Miniplot):

- Open ending, internal conflict, multi-protagonists, passive protagonist

Anti-Structure (Antiplot):

- Coincidence, nonlinear time, inconsistent realities

McKee also identified Nonplot - films that "dissolve into portraiture" and fall outside the story triangle entirely. These works "inform us, touch us, and have their own rhetorical or formal structures" but "do not tell story."

Key insight: Each choice communicates theme and affects audience expectations. Classical design serves commercial genres, minimalism explores character psychology, anti-structure challenges conventional storytelling, and nonplot moves beyond story into pure portraiture.

McKee showed that structural choices aren't just technical decisions but artistic statements about how the world works.

Beyond These Examples

The structural approaches we've covered represent only a small selection of available screenplay formats. These primarily Western, Hollywood-influenced frameworks have dominated mainstream film and television.

Many other storytelling traditions and approaches exist, including:

- Kishotensketsu (Japanese four-act: Introduction → Development → Twist → Conclusion, no conflict required)

- Essay development patterns (increasing importance, complexity, comparison/contrast, cause-and-effect, etc.)

- Circular/spiral structures from various cultures

- Collective narratives that follow groups rather than individuals

- Episodic structures without overarching plots

- Stream of consciousness approaches

- Modular storytelling (separate pieces that connect thematically)

- Multiple timeline structures

- Anthology formats

The landscape of story structure is vast and constantly evolving. What we've explored here gives you a foundation, but countless other tools and approaches are waiting to be discovered or invented.

Structural Options

Story structure is flexible. These approaches we’ve covered are just some of the tools available - there are many more out there. You can have 2 acts, 3 acts, 4 acts, 5 acts, or however many work for your story. You can structure your story as:

- A series of short stories all building into a complete story

- Separate standalone pieces that connect thematically

- Anthology format with independent segments

- Stories within stories

- Many acts, few acts, whatever serves your purpose

The key is figuring out what works best for what you’re trying to achieve with your story.

Finding Your Approach

The most important work is understanding your story’s idea and what you’re trying to achieve. Once you know that, you can determine which structural tool works best.

These different approaches are tools in your toolkit. Some might work better for certain stories, others for different ones. There’s no formula - it’s about matching the right tool to your goal.

Key Takeaways

- Multiple structural approaches exist - and there are many more beyond what we’ve covered here

- These are different tools for different jobs - figure out what works best for your story

- Understanding your story’s core idea is essential - know what you’re trying to achieve

- Structure is about intentional organization - make conscious choices about how to arrange your story

- No formulas or rules - it’s about finding the right tool for what you’re trying to accomplish