Film 210: Week 4

Descriptions

In this lesson, you'll learn:

- The difference between narrative description and element descriptions

- The golden rule of brevity in screenplay description

- How to effectively describe characters, settings, objects, and actions

- How to integrate these descriptions seamlessly into your screenplay

Let's begin.

In screenwriting, the term "description" can refer to two related but distinct elements:

- Narrative Description - This is the entire area of text between scene headings and dialogue, sometimes called the "action" or "scene description" section of the script. This is where all visual elements are described.

- Element Descriptions - Within the narrative description area, we craft specific descriptions for different elements of the story: characters, settings, objects, and actions.

This lesson focuses on effectively describing these key visual elements within the narrative description portions of your screenplay.

The Golden Rule: Brevity

When it comes to description, the golden rule is brevity. Think of words as precious screen time—use them wisely to maximize impact.

Concise writing allows your audience to effortlessly read your script, maintaining momentum and engagement.

Sometimes, we must tailor our story descriptions to their story significance, but overall, when crafting descriptions:

- Aim for one-sentence descriptions when possible

- If more detail is crucial, never exceed 3-4 lines

Element Descriptions

1. Character Description

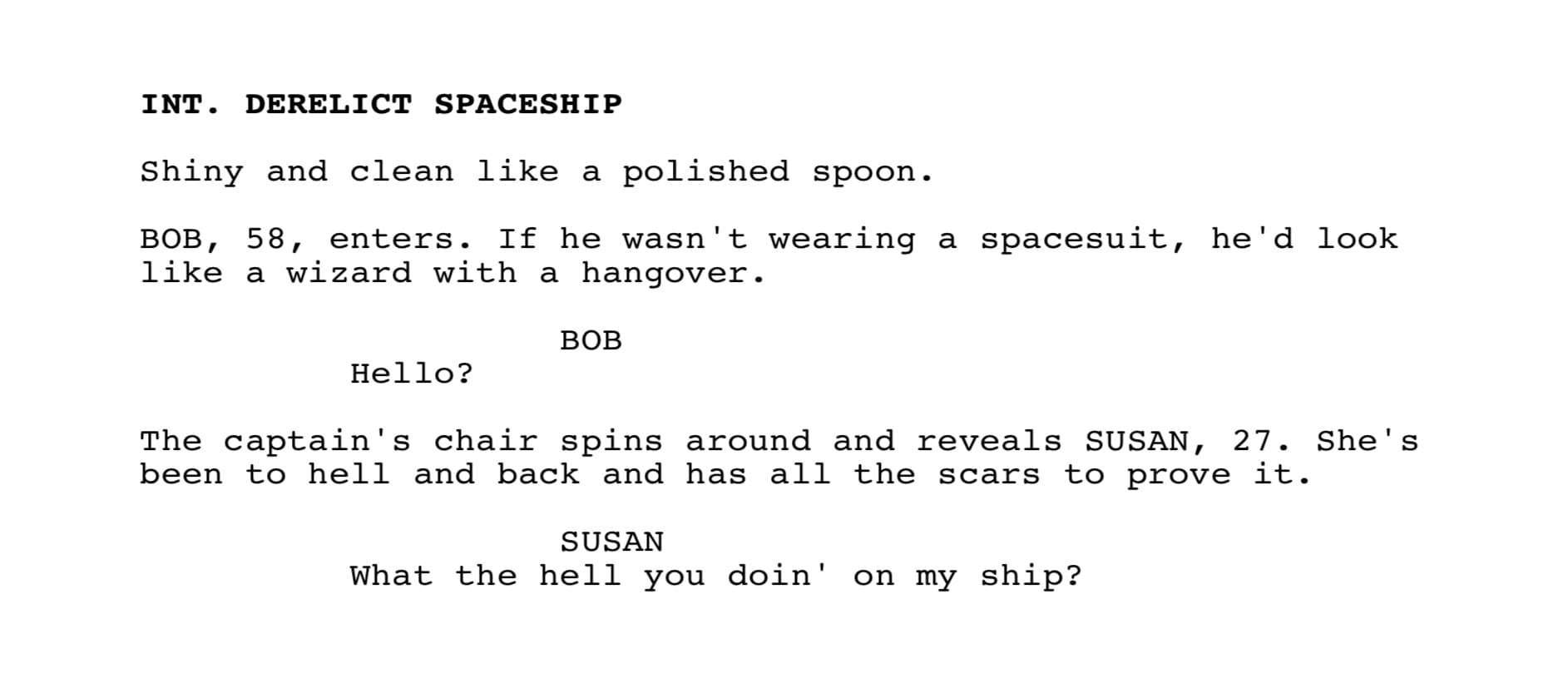

Most characters need an introduction when they first appear in the script.

Use ALL CAPS, but only when they are first introduced. If a group or character isn't essential to the story, you do not capitalize them.

Describe their essence with a few vivid details.

Understanding Character Essence

When we talk about a character's "essence," we're referring to their core identity—who they truly are beyond surface details. Physical attributes, clothing, or occupation alone don't reveal the essence; it's how these elements reflect deeper personality traits that matter.

Think of essence as answering questions like:

- What makes this character unique?

- What fundamental trait drives their behaviour?

- How do they move through the world?

- What impression do they leave on others?

For example:

- "A tall man in a suit" → physical description without essence

- "A man who wears his expensive suit like armour" → reveals essence (protective, defensive, status-conscious)

- "A lawyer" → just an occupation

- "A lawyer who treats courtrooms like battlefields" → reveals essence (combative, dramatic, sees law as warfare)

When you describe clothing or occupation, always ask: "What does this reveal about who they are underneath?"

Focus less on a character's physical details and more on their distinguishing personality (e.g., boring, angry, ruthless).

It can be helpful to connect a characteristic to a visual, either through a metaphor or comparison.

For example:

- NELSON CONRAD, 68, waddles like a deflated beanbag chair. (Movement reveals defeated nature)

- ELENA CAMBRIDGE, 34, a predator dressed in Giorgio Armani. (Clothing enhances personality, not just fashion)

- TIFFANY ARCHER, 25, is as emotional as a piece of paper. (Comparison reveals fundamental character trait)

Notice how we focus on their essence, not physical details. Physical details (e.g. blonde, tall, thin) can limit the selection of actors to play them. The ideal actor may be someone who doesn't fit the physical characteristics.

Also, don't focus too much on what they wear. That's the role of the costume department. (Yes, I mentioned Giorgio Armani above, but that is to suggest someone wearing expensive clothes and not the colours or particular pieces she's wearing.)

Names are important. First names and last names identify a complete identity.

Age is also important. "Sandy, 28" is different from "Sandy, 94." Be specific. A person in their mid-20s could be 23 or 27. That's a big range of growth for some people.

Use words that describe how they move, stand, and present themselves.

Consider giving your characters a job, especially notable characters.

Note: Characters must only be introduced in ALL CAPS with a description the first time they appear in your script. For all subsequent appearances, use their name in regular caps.

Character Do's

- Use ALL CAPS for important characters' first appearance.

- Describe their essence with vivid details.

- Focus on distinguishing personality over physical details.

- Use metaphors or comparisons to qualify characteristics.

Focus on

- Full name

- Specific age

- Descriptive movement or presentation

- Occupation (for notable characters)

Character Don'ts

- Using limiting physical characteristics.

- Using actors' names.

- Comparing them to other characters in books or movies.

- Identify them as the protagonist or villain.

More Examples of Character Descriptions

- MAX, 17, is a pirate in ripped jeans. (Juxtaposes youth with rebellious identity)

- MARK ZUCKERBERG is a sweet-looking 19-year-old whose lack of any physically intimidating attributes masks a complicated and dangerous anger. (External appearance contrasts with internal quality)

- WARDEN SAMUEL NORTON strolls forth, a colorless man in a gray suit and a church pin in his lapel. He looks like he could piss ice water. (Metaphor reveals cold, harsh nature)

- In the center of a mess of quills, paper, and books, JEAN, 24, sits and enjoys a small feast at his desk. He is a portly man, the third son of a noble, and his chin is stained with wine and pig grease. (Environment and details reveal indulgent, privileged character)

- FIONA, 23, whose usually unruly hair has been tamed just this once, sits on her living room couch. (Detail suggests special occasion and normal character state)

- GWEN, 23, stands in the open doorway with her bags under her arms. Organized to the extreme, the apartment is her nightmare. (Reaction to environment reveals character trait)

- RICK, 22, leans against the kitchen counter. He wears the hollow smile of a man who hasn't had enough sleep. (Expression reveals inner state)

- EVELYN COLLINS, 17, who exudes confidence and carries herself like the CEO of her own destiny, walks into the cafe. (Movement and comparison reveal personality)

- JEELA (17), who could tell why you were wrong before you even finished the sentence, packs a suitcase filled with more books than clothes. (Action and detail reveal intellectual character)

- TOM (35) wears a shark tooth necklace proudly and walks a fine line between arrogance and confidence. (Accessory and movement suggest personality)

- MARIA (25) braids the young girl's hair. Her heavy makeup does little to disguise the exhaustion on her face. (Detail reveals struggle beneath appearance)

- WILLIAM (38) sits in one of the chairs. He is a shark in blood-infested water, perfect for a defence lawyer. (Metaphor connects personality to profession)

2. Setting Description

When introducing new locations, let us know where your scene takes place. Do not convey this in the slug line. Slug lines should be minimal and straightforward.

Add a short line of description, similar to how you would describe characters. Focus on capturing the essence of the place. Brevity is a strength.

Even if it's a place we might know (e.g. the suburbs), a good description can communicate tone, mood, and context:

Main Street, USA. Beneath the Fourth of July parades, high school football glory, and blue-ribbon apple pies at the county fair lies the heart of the real American Dream.

However, if it were something like this, it would become a different story:

Main Street, USA. Despite the Fourth of July parades, high school football glory, and blue-ribbon apple pies at the county fair, whispers of foreclosures and shuttered factories linger on the outskirts of town.

Specifying the month can convey mood. New York in October is different than New York in July.

A story not set in the present may need more description, especially if it is unfamiliar to modern culture.

1350s. Medieval Europe. The Black Death ravages the continent; castles evolve, the Hundred Years' War rages on.

It often helps to assign a specific year, especially if it isn't set in our time. This prepares the reader for the changes described.

If the story is set in an obscure or unique location, briefly describe the scene so that the reader can visualize it clearly.

Only show details if they impact the characters. A radical new political system isn't vital to a character lost in the desert.

Note: Locations only need to be described fully when first introduced or if something significant has changed in later scenes.

Location Do's

- Introduce new locations with a brief description

- Capture the essence of the place concisely.

- Use description to convey tone, mood, and context.

Tips

- Specify the month to convey mood

- Assign a specific year for non-contemporary settings

- Describe unique or obscure locations briefly but vividly

- Focus on details that impact characters

3. Object Description

Showing unique objects helps describe them. However, the danger is not to over-describe an object.

Give the essence of the object explained in a sentence.

Focus on what it might look like in our world—a gun, a camera, a car. Use character interaction to describe its purpose. Sounds can also be helpful.

Gary grabs the Optithon, a weaponized telescope that fits in the palm of his hand. He aims—WHOOSH— a laser shoots out, and Paul is vaporized into dust.

Also, remember, like characters and settings, unique objects only need to be described the first time they appear in your script.

Object Do's

- Describe unique objects concisely

- Focus on real-world comparisons

- Use character interactions to show purpose

- Incorporate sounds when relevant

4. Action Description

Action descriptions detail what characters do in a scene—their physical movements and behaviours that appear on screen. While setting descriptions establish where we are, action descriptions show what happens there.

Action Do's

- Use active, precise verbs (e.g., "sprints" instead of "runs quickly")

- Keep descriptions lean - only what we can actually see on screen

- Vary sentence structure based on pace - short sentences for quick action, longer for deliberate movements

- Use white space effectively - break up action into digestible chunks

- CAPITALIZE important sounds and props when first introduced

Action Don'ts

- Using "begins to," "starts to," or "tries to" - either an action happens or it doesn't

- Using passive voice and continuous "-ing" verbs when possible

- Directing the camera or telling us what we "see"

- Describing emotions or thoughts unless visually apparent

- Using exact measurements like "ten feet away" - use visual references instead

Examples:

Mike tosses the files onto the desk. He paces the office, checking his watch every few seconds.

The phone RINGS. He lunges for it.

This conveys character behaviour, emotion, and movement without explicitly stating feelings or using camera directions.

Putting it all together

When introducing new elements in your screenplay, there's a logical sequence that helps readers quickly understand the scene without confusion. The faster you establish each new element, the less chance there is for misunderstanding or for readers to create their own incorrect mental images.

A precise introduction sequence helps your reader immediately visualize your story world:

- The SLUGLINE establishes a basic location and time

- SETTING DESCRIPTION provides immediate context for where we are

- CHARACTER INTRODUCTIONS show who's in the scene and what they're like

- OBJECT DESCRIPTIONS highlight essential items as they become relevant

- ACTION DESCRIPTIONS show what's happening in the scene

For example:

INT. CORNER DINER - NIGHT

A 24-hour refuge of cracked vinyl and flickering fluorescents.

SARAH KLEIN enters, scanning the nearly empty diner. She straightens her blazer and approaches the counter.

MIKE DAWSON, 40s, an accountant with boxer's hands, hunches over coffee. He repeatedly checks his watch.

Mike's hand moves to the MANILA ENVELOPE beside him, thick with documents.

This sequence quickly orients the reader to where we are, who's there, what significant objects matter, and what's happening. Once these elements are established, the scene can proceed with dialogue and continued action.

Key Takeaways

- Understand the different types of descriptions - Know when and how to use character, setting, object, and action descriptions

- Follow the golden rule of brevity - Keep descriptions concise, never exceeding 3-4 lines for any single element

- Focus on essence over details - Capture what makes characters, settings, and objects unique without over-describing

- Use active, visual language - Write in present tense with strong verbs and visually specific details

- Introduce elements only as they appear - Describe locations, characters, and objects at their first appearance

- Avoid directing on the page - Let your descriptions inform without dictating camera angles or specific blocking

- Create a cohesive reading experience - Use descriptions to maintain story flow and reader engagement