Film 210: Week 9

Actions and Responses

In this lesson, you’ll learn:

- How actions and responses form the foundation of compelling storytelling

- Why these elements are the heart of character development and conflict

- How to structure story beats using action/response patterns

- Techniques for using try/fail cycles to create momentum

- Why mastering actions and responses separates human storytelling from AI

- Specific methods for revealing character through actions

Let’s begin!

Refresher

When I first introduced the storytelling framework WOARO (want, obstacle, action, response, outcome), I said that actions are the things a character does or says (or doesn’t do or say) to get what they want.

They are active verbs that can be done to someone else (also known as transitive verbs): Tom hits Bill, or Sally kisses Greg.

They can be the physical actions they take or the dialogue they say. These are both actions..

Two Types of Actions

When we talk about actions in storytelling, we’re discussing two different but connected concepts:

Script Actions: The literal, physical actions and dialogue you write on the page. “Tom hits Bill” or “Sally says ‘I love you.’” These are the concrete verbs that describe what happens moment to moment.

Strategic Actions: How your character tries to get what they want. Tom might be trying to intimidate, while Sally might be trying to seduce. These are the underlying approaches characters use to pursue their goals.

Both matter. You need to know what strategic action your character is pursuing (intimidating, charming, pleading) so you can choose the right script actions to show it. A character trying to intimidate might slam a door, speak quietly, or loom over someone. A character trying to charm might smile, offer a gift, or tell a joke.

The strategic action drives the choice of script action.

Action/Response

Actions don’t stand on their own. There’s always a consequence, always a response. Like want and obstacle, actions and responses are two sides of the same coin. One character’s action is often the response to another character’s action.

Either action or response can occur first:

- Action/Response: A character takes an action, and an internal or external force responds.

- Stimulus/Response: An internal or external force takes an action, and the character responds to it.

In real life, we often go through a sequence of actions and responses:

- An internal or external stimulus occurs

- It leads to an internal emotional response

- Which prompts a thought (“How will I respond?”)

- We choose to act (and/or vocalize) or not act.

In your story, you must show your characters’ actions and responses at every step. The moment you stop showing action and response, you stop showing the dramatic nature of the story. This dynamic is the essence of “show, don’t tell.”

A note on emotions: While emotion is a response, we typically only write it when it impacts the story’s direction (either the character’s future actions or another character’s responses).

We leave emotion to the actor’s interpretation. They’ll often bring more nuance and care than we can ever write.

The Heart of Conflict

This dynamic between action and response is the engine that makes the story work.

Characters act or respond to stimuli, leading to further actions and responses.

We never know how it will turn out, and it constantly feeds back on itself. Actions lead to unexpected responses, and responses lead to unpredictable actions. Each moment interacts with every moment before and after it.

It creates uncertainty, conflict, and struggle, making stories engaging and exciting.

Action/Response as Story Beats

The interaction between an action and a response is a story beat. It involves a character who wants something and takes action to get it, which leads to a response, which leads to another action.

action + response = story beat

A story beat advances when a character tries a different action to achieve something or responds differently.

For this reason, we can apply the definition of story beats to any moment plotted across a narrative. They define the shape of any sequence, act, story, or series, but for this discussion, we’ll focus on their smallest form within scenes, shaped by actions and responses.

Beats vs Beat

We need to distinguish between the two versions of beats in storytelling:

Story Beat: A unit of action, either in a scene or story, that represents an event, plot point, or step that moves your character towards their outcome. In a romantic comedy, the protagonist asking out their love interest for the first time would be a story beat.

Pause Beat: A momentary pause indicated with a parenthetical written into a script. This form can be considered directing and may be ignored by directors and actors. You may want to consider not using it.

Throughout this lesson, we focus on story beats, which are essential to crafting compelling narratives and are less likely to be disregarded in production.

Story beats within a scene

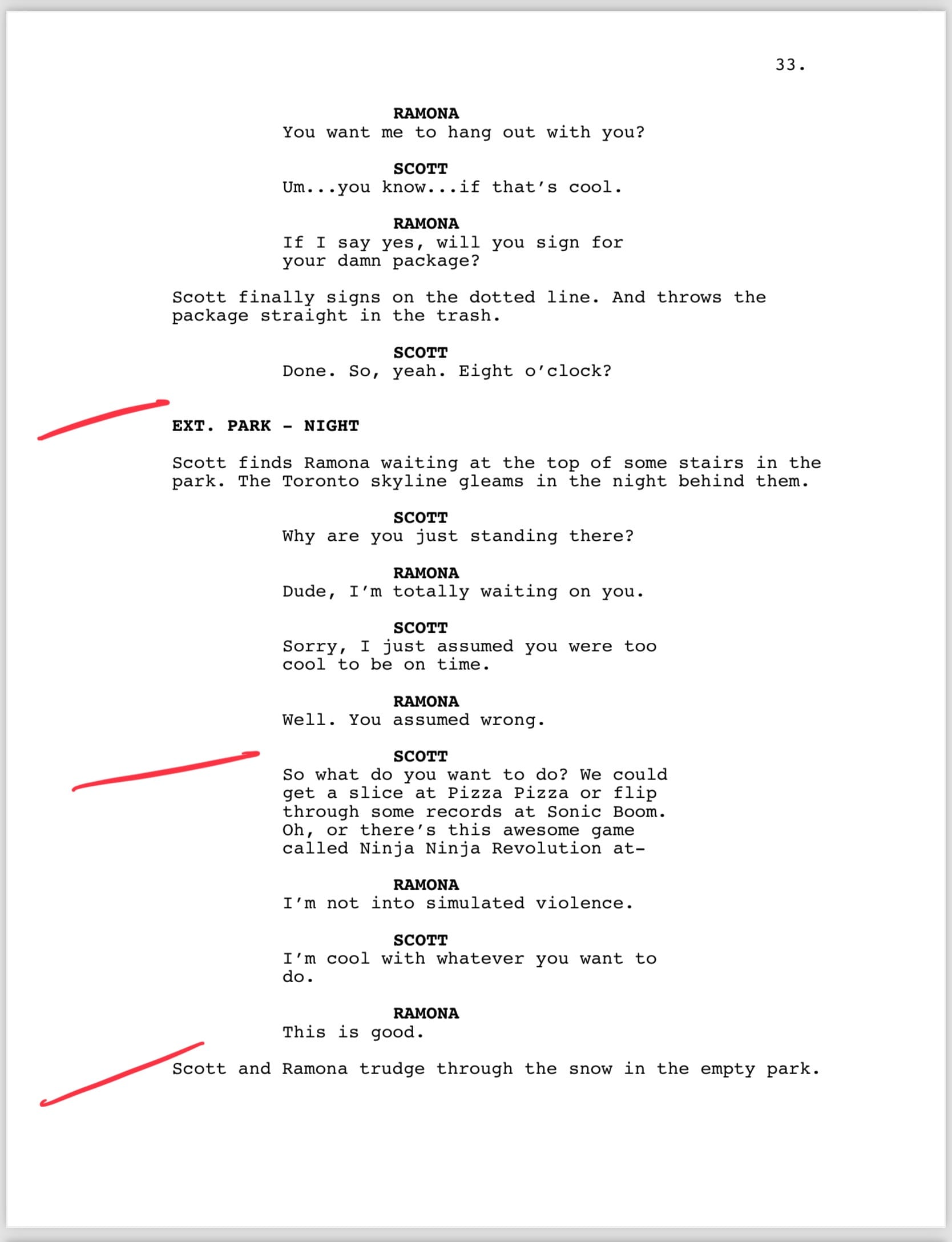

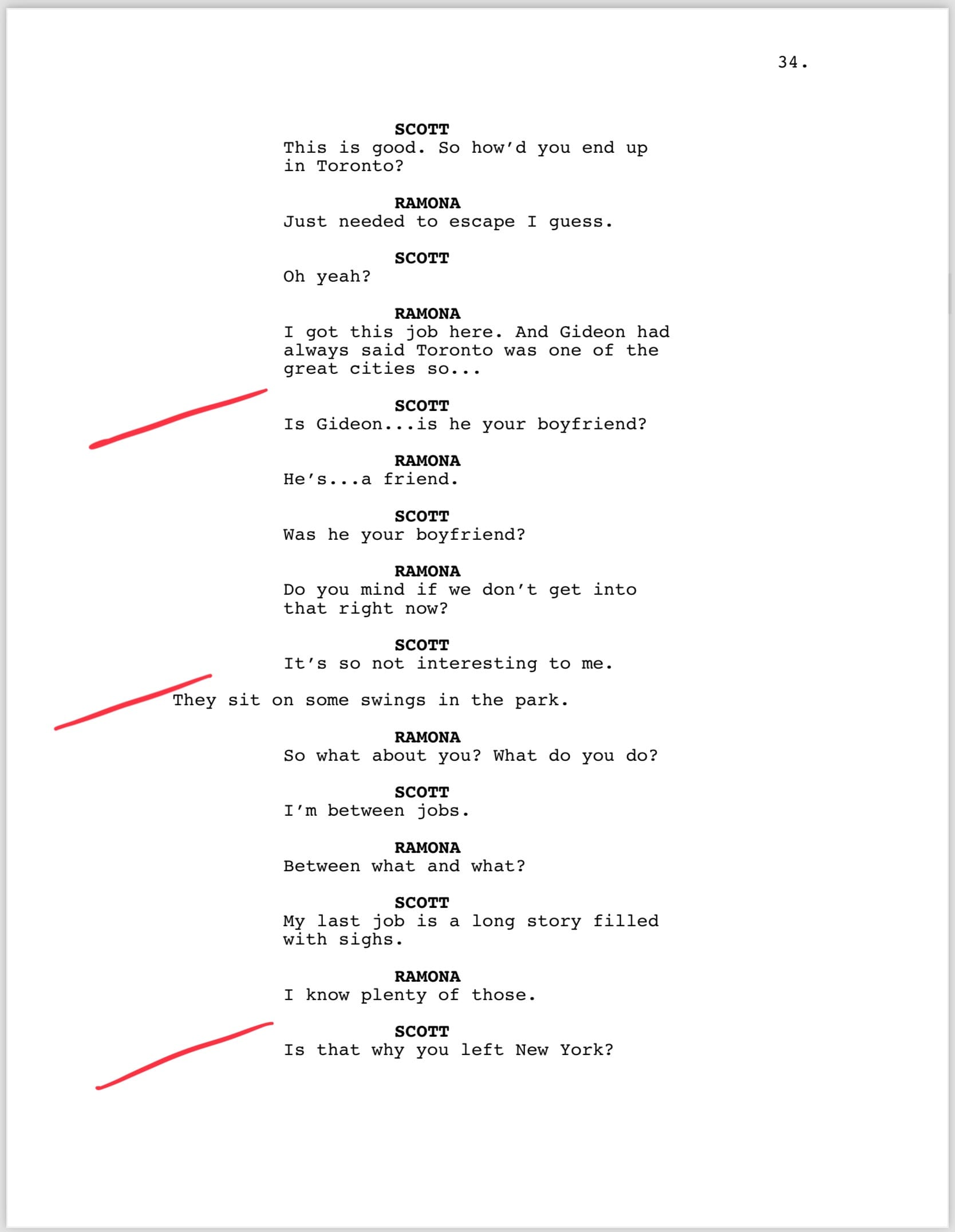

Look at these two pages from Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, written by Edgar Wright and Michael Bacall and based on Bryan Lee O’Malley’s graphic novels.

Script pages from Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

Until this point in the script, Scott has been trying to meet Ramona and ask her on a date. This scene is about them getting to know each other. Scott drives most of the scene, asking questions and trying to learn about Ramona. Much of Ramona’s action deflects his curiosity.

Many beats are built around him asking a question and her countering it, before he asks another question. Each new beat is him trying a new tactic to learn about her.

On the second page, she tries to ask him a question and turn the focus to him, only for it to return to her, and he regains control.

Each story beat is built around their intentions (discovery vs. guarded), and the actions and responses keep the story focused and moving forward.

Try/Fail Cycles

It’s helpful to think of actions and story beats as try/fail cycles, an idea I learned from Mary Robinette Kowal.

Your character will try different actions to solve their problem but must continually fail. These failures come in two forms:

- Yes/but - Yes, the hero succeeds, but a new problem emerges.

- No/and - No, the hero fails, and a further complication occurs.

Each of these try/fail cycles continues to progress the story forward.

The story ends when they resolve the problem with a try/success cycle:

- Yes/and - Yes, the hero succeeds, and an additional thing now happens.

- No/but - No, the hero fails, but something positive occurs to move the story forward.

Try/fail cycles are powerful tools to adopt into your writing practice. If you apply this to what I said about WOARO, you can use it to the smallest story beat and across scenes, screenplays, or seasons.

Actions and Responses Revealing Character

The specific actions a character takes or how they respond can reveal much about who they are. For example:

Two men have the same goal: to make money.

- One works as a bank teller from 9 to 5.

- Another robs the bank.

Both aim to get money, but their very different actions reveal vastly different aspects of their characters.

Be as specific as possible

Even within a single concept, a wide range of specific actions can reveal different aspects of a character.

The bank teller might pick up extra shifts, enroll in night classes, or start a side business. The bank robber could meticulously plan for months, threaten staff with a weapon, or negotiate with hostages.

However, actions can also show character change—perhaps our bank robber refuses to use a gun, but after a heist gone wrong, he picks up a weapon to escape. Maybe, even worse, our bank teller decides to rob his bank. These changing actions reveal character growth or downfall.

Why AI Struggles with Actions and Responses

Humans are complex. We say and do things contrary to what’s always right because we are buffeted by wants, emotions, and thoughts that make us respond in unique, unexpected, and sometimes incorrect ways. This leads others to respond similarly, and AI has a hard time replicating that.

Action and response are where emotion and experience lie. They’re what people connect to. This is where your natural storytelling voice lives, and AI can’t replicate it.

I am okay with using AI as a starting point, but then you must dig deeper. Work the scene, rewrite it, and improve the actions and responses. If I find your storytelling boring, trite, unexciting, or unsurprising, it’s most likely because you stopped at AI’s first draft instead of exploring your character’s actions and responses.

Key Takeaways

- Actions and responses are the heart of all stories—they drive narrative forward, reveal character depth, and create engaging conflict.

- Every action needs a consequence or response—this dynamic is the essence of “show, don’t tell.”

- Specificity in actions and responses defines your characters and separates compelling storytelling from predictable writing.

- Try/fail cycles help structure story beats effectively and create forward momentum.

- Actions and responses are where emotion and experience reside—this is what audiences connect to and where AI consistently fails to replicate human authenticity.