Lesson: Character and World-Building

Now that we've spent weeks cutting back our descriptions and directing, we'll look at some ways to use WOARO and standard script form to reveal these details in character and world-building.

Building characters

Before we build them into the script, let’s look at how we can figure out some of the details and nuances of them.

We’ll look at:

- Character outline lists

- An actor’s approach

- Building from theme

- WOARO

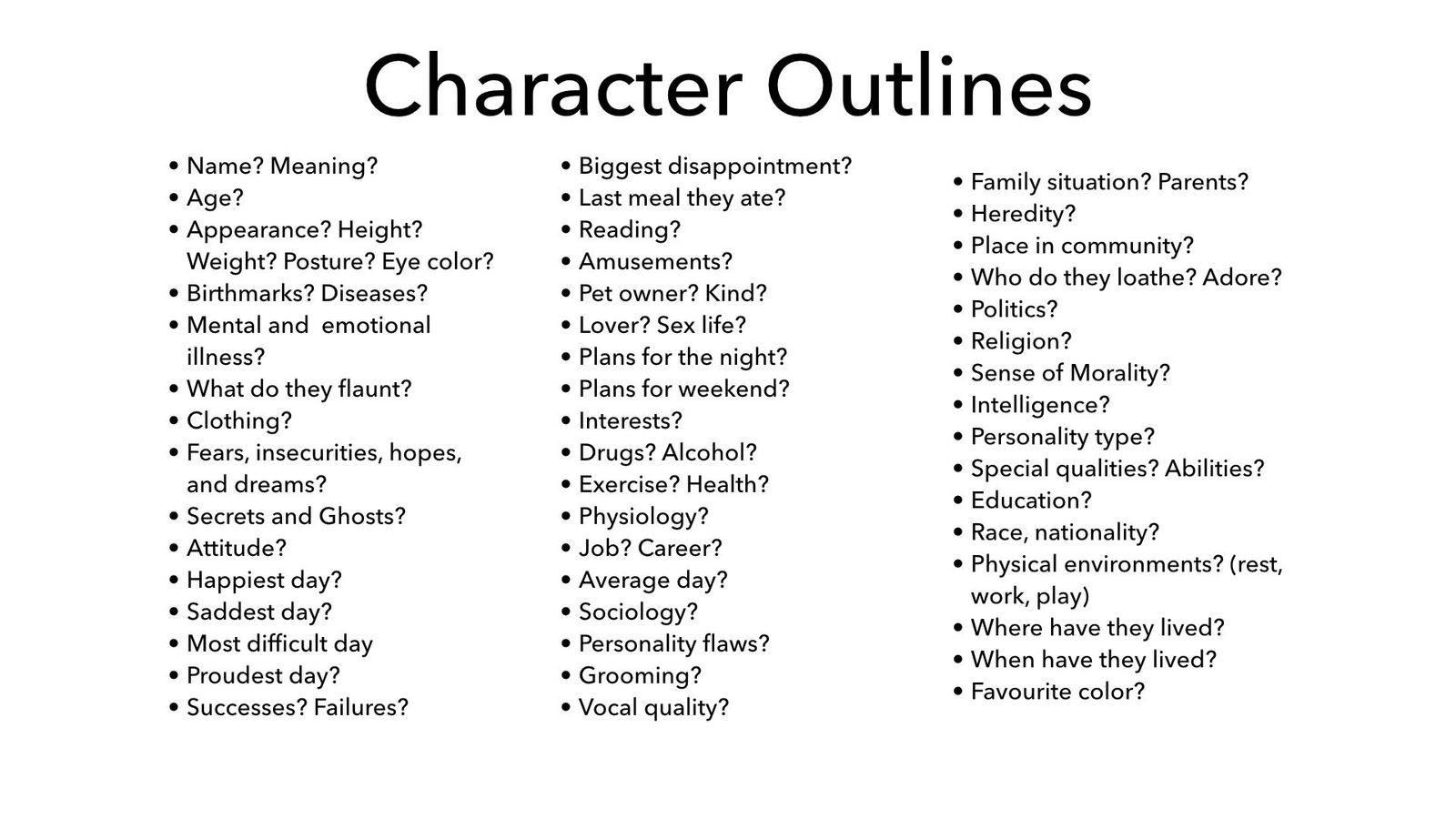

Character outline lists

We can work from character outline lists, where we answer specific questions about a character’s individual traits.

You can take this as far as you want, focusing on the physical characteristics and small details, such as what they have in their purse, wallet, or pockets. This exercise is one where you can go to the furthest extremes.

You could also build this out with mind maps, timelines, scrapbooks, and other various methods.

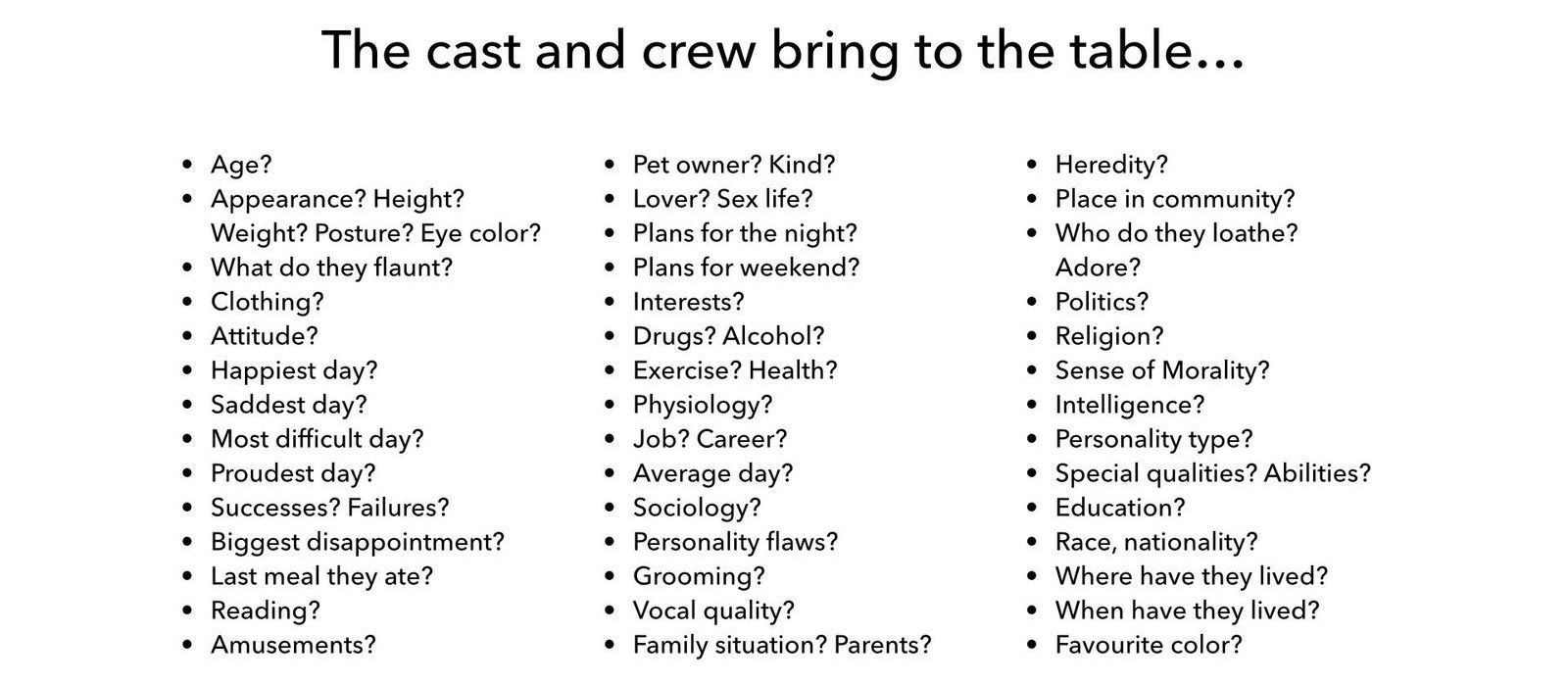

However, as you know from the previous lessons, I caution against this because so many details will be altered or added by your cast and crew.

This view is from my years in film production, where I have seen scripts, scenes, and locations pulled apart in the process.

So I want you to consider how much time, energy, and emotion you put into your choices because things change so much.

An Actor’s Approach

Some actors will break a script and search for details that will answer some of the following questions:

- A character’s spine: we discussed this with interior want, but it is what each character wants within their lives. How does this want to drive them through the story?

- Obstacle/Issues: What keeps them from it? Do any flaws hold them back?

- Action Verbs: Remember this about specificity. How does your character get what they want?

- History/Backstory: What events in your character’s past shaped them into who they are?

- What just happened: What happened to a character moments before they entered the story?

- Relationships: What relationships does your character have? What shape are they? Are they high or low status within it?

- mentors or allies

- sidekicks

- love interests

- family (parent, child, sibling, etc.)

- evil mentors

- henchmen

- tempters/temptresses

- Images/objects: this can be related to their physical being and environment, but it can also be what images and objects hold meaning (either negative or positive).

- Belief or Worldview: What do they believe in? How do they perceive the world? These could also be obstacles because they’re misperceptions that hold them back.

- Ghosts & Secrets: What haunts your character? What secrets do they hold?

- Skills & Traits: either physical, mental, or emotional.

- Habits: positive or negative

You could use these questions to fill out the details of your characters.

Notice how this approach looks at the characters from an empathetic point of view.

The best actors never approach their villain roles in a negative light. They find justification in their actions as to what needs to be done in order to achieve their higher goals.

Building from theme

As we discussed in the previous lesson, the theme can be built out of character or plot, so it’s not hard to reverse this and build the character from the theme.

Once you have your premise, you’ll likely have a sense of your protagonist, as well as the antagonist of the story that stands in the way of them achieving their goal. From here, you can work on their opposing worldviews and identify a possible underlying thesis of the story.

Once you have that, ask yourself what are the different viewpoints and groups that develop from these three sides:

- those who agree with the thesis statement.

- those who disagree with the thesis statement.

- those that are indifferent to the thesis statement.

Then start exploring relationships like the ones above—mentor/allies, sidekicks, love interests, family, evil mentors, henchmen, and tempters—and adding more characters if needed.

As well, the theme can be a reflection of what a character wants or is a representation of their weaknesses or flawed perceptions of the world. These are the obstacles a character must overcome to achieve what they want in life.

Consider where these flawed beliefs come from. Was it a part of their backstory? Their environment? From the events of the story? All of these are statements about your theme.

Similarly, what motivates them to change? What is their want? Where does it come from? Again, their backstory, their environment, or the events of the story?

Lastly, consider symbols, imagery, and thematic elements that can shape a character's dialogue, appearance, or quirks:

- their mood

- their objects (jewelry, weapons, creatures)

- anecdotes and stories of their past

- phrases and vocabulary

- quirks and traits

- names

Not only can these represent the themes of the story, but also the character’s fatal flaws, wants, and motivations.

WOARO

Finally, let’s discuss WOARO. Many aspects of the character can be approached through its prism.

- What does your character want (internal and external)?

- What obstacles stand in their way (internal and external)?

- What actions do they take, and how do they respond?

- How are they described?

These questions can help shape your character—right from the first page of your script (and if you take internal wants and obstacles into account, long before).

Placing your characters in action forces you (and them) to make choices about who they are. Whether you outline beforehand or work on it the day of writing, it is ALWAYS about making choices.

Want and Obstacles

Above all else, a character is defined by their wants, both internal and external.

The outer goals drive the story, but they are also driven by their inner desires that extend over a lifetime. These are the big goals of life and are defined by your character's history.

Similarly, external and inner obstacles shape a character's journey, standing in the way of what they want and holding them back.

As well, a character's wants and obstacles also define their allies, friends, and enemies.

Want and obstacles are the bedrock of your character and story. If the choices you make here shift, then it fundamentally affects both. The sooner you commit to this choice, the easier your writing will become.

Action and Response

It's important to remember that the actions a character takes or how they respond (what they do or say, or don't do or say) define them. They are a reflection of the engrained behaviors built upon years of experience and history.

Action is always done with the intention to confront change—either to stop it from happening or to create it. It can be done involuntarily or by choice—and both of these options define your character.

Also, remember that actions depend on specificity. Knowing exactly how your character loves, hates, defends, and responds defines them.

This specificity will also include the words a character uses. Are they eloquent, crass, or pandering? Do they talk down to some people, but not others?

Similarly, how does your character respond? Whether a character responds immediately to stimuli or thinks about it before responding, and how they respond all are indicators of their personality.

Action and response is also a big indicator of emotion—even if we can't show it in the script. If a character fights back or runs away will tell us something about their emotional response. If they don't react also tells us something.

Lastly, if the field of your character's actions or responses changes, then it represents character change. For example, a character who shifts from love for another character into hate.

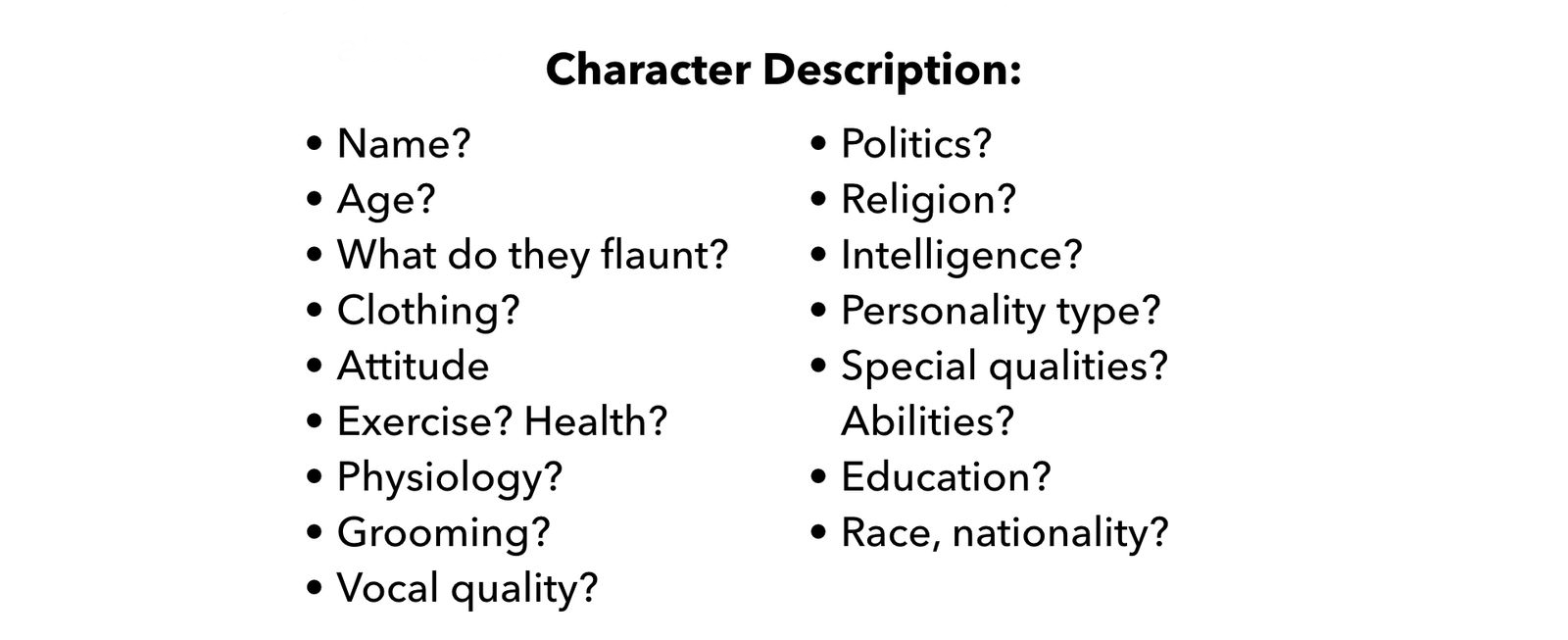

Character descriptions

And lastly, character descriptions, which we've covered quite a bit.

Remember, this is more about their essence and less about physical traits or backstory.

When they first physically appear in your story, what is it that we need to know about their character?

Notice what we can hint at just through that description.

World Building

Similar to character building, the danger of excessive world-building is that it doesn't make its way onto the page or screen, or the cast and crew will toss it aside to pursue their own vision.

But that doesn't mean that we still can’t consider it and bring certain elements into the script.

Some ways we can approach it:

- world lists

- building from themes

- discovered in the process

World List

Similar to the character list, we can consider different aspects of our world to build it out:

- Place and Architecture - What is the geography and climate of this place? What resources do they have? How does the architecture of the place relate to it?

- Life - What does a normal day look like for the people in your world? If there is a class system, what is it and how do the citizens interact daily?

- Language - How do they communicate? (Of course, be cautious with this since creating a language too complex may become a hindrance to the story-telling.)

- Art and Culture - Is there art in this world? What sort of art? How is it viewed by the intellectuals and the masses?

- History - What are the key, relevant events that led to the beginning of your story? What has built it up? What has hampered it?

- Science & Technology - What role has technology played in the development of this society? What has been discovered? What hasn’t?

- Law - What system of rules exist? How is it enforced? Is it working?

As you explore these details, ask yourself how they connect. How has history impacted art and culture? How has science and technology impacted architecture and vice versa?

Building from themes

Again, consider what symbols and thematic elements can be adopted into your world:

- objects

- iconography

- vocabulary

- names

- specific locations and places

- weather

Not only does every place carry meaning within the history and culture of a world, but also in relation to each and every character.

Discover character and world details in the process of writing

The story is built by our choices, either before we begin writing or along the way. Often it is easier to consider these details in the process of building the story and rewriting it so that we don’t invest too much energy and time in work that gets lost in the filmmaking process.

Placing world-building into your script

First, you can use the opening descriptions of places, as well as the descriptions of objects and characters to show elements of the world. Keep them tight, allowing only a maximum of 3-4 lines for each—but of course, fewer words are always better.

You can also bake good world-building right into the WOARO mix.

- The wants of characters can show what is of value in this world.

- Obstacles can not only show the conflict between groups but also the elements that threaten the hierarchy of needs of your characters (physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, self-actualization).

- Actions and responses can highlight the language, the tools, the rules, and the everyday existence of your characters.

Every character and every interaction has an opportunity to reveal information about this world.

Develop a set of rules

A helpful idea is to develop a tight and clear set of the most important rules of your world. Some can be broken and some cannot. For example, social rules can be broken, but gravity can’t.

Some rules to consider:

- rules of magic or rules of science

- rules of the hierarchy and the roles within it

- rules of the natural world

- rules of individual characters

What happens if you break some rules? What are the consequences? How do the rules create limitations and edges to your world?

When you write your story, don’t explain the rules. Show them in action—the sooner the better. Show the edges and what happens when some rules are broken.

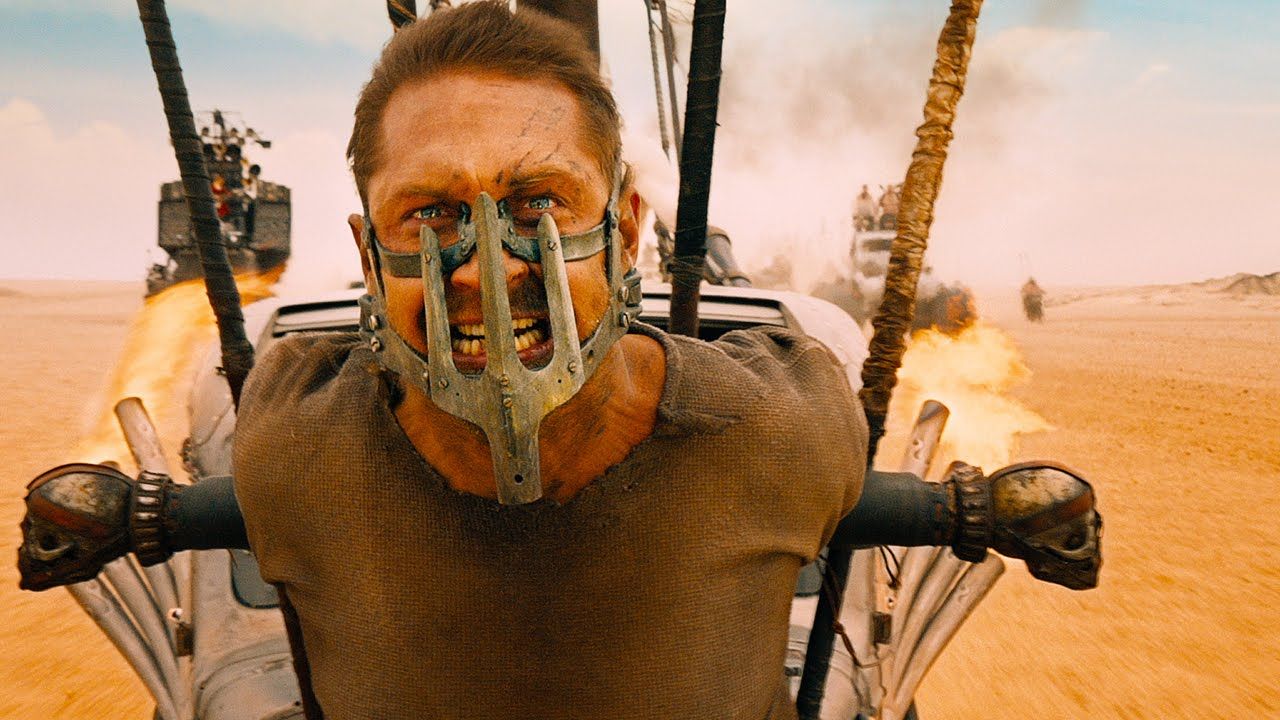

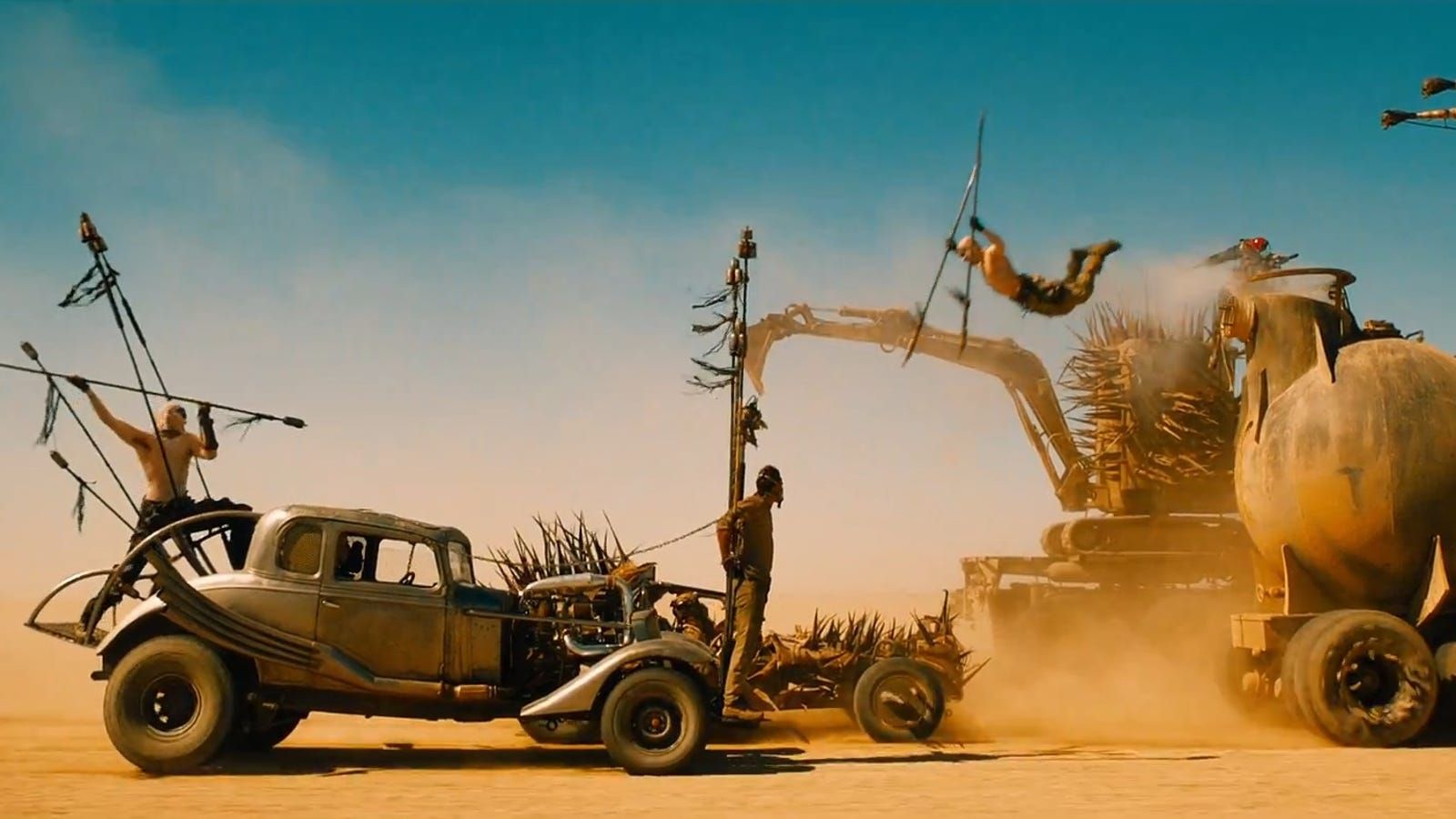

An excellent example of world-building through showing and action is Mad Max: Fury Road. Every scene and every moment provides information and corners of this world that contain meaning—yet the story doesn’t pause to explain it, but continues its relentless pace.

Mad Max: Fury Road

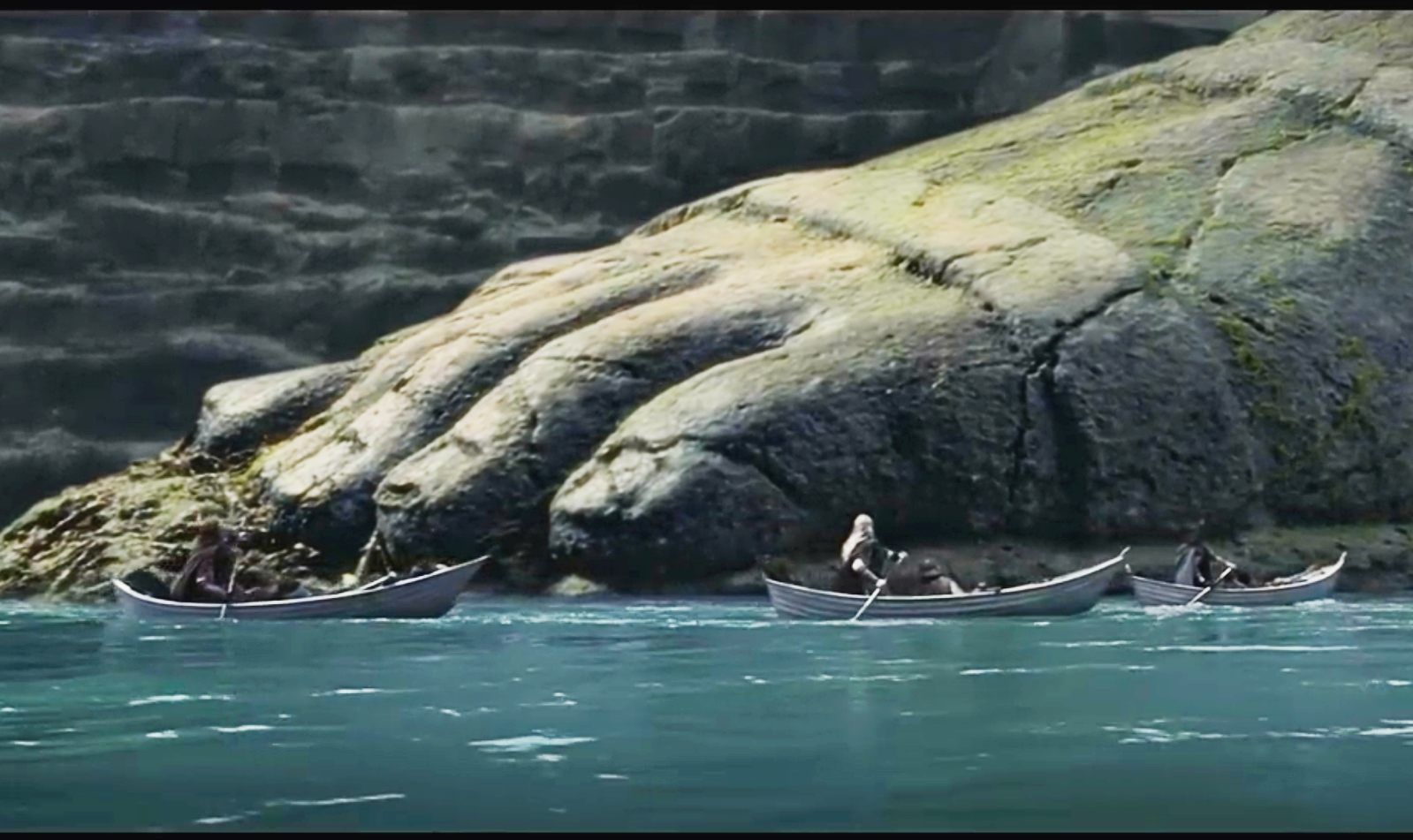

Another example is the Lord of the Rings trilogy, where large statues cover the landscape. They communicate a deep history to the world, without telling us the specifics.

Think about how you can reveal the deep history, art, and architecture of your characters and worlds without telling us.

Statues in the Lord of the Rings

So what you may put on the page may not end up on the screen.

Assignment

In 2-3 pages, write a script that builds a unique world and the characters within it through the use of WOARO. Don’t make it ordinary. Change at least one detail or aspect of how it is different from our world.

If you or your characters start telling the reader information in any manner then you have done this exercise wrong—show, don't tell!

Have fun with this one!

Marking Criteria

- Written in the active, present tense.

- Proper screenplay format (including sluglines, parenthesis, and ALL CAPS on the introduction of characters).

- Proper use of descriptions.

- Includes a title page that uses the proper format.

- Only five errors are allowed on each script.

❗This assignment is due Sunday, Nov. 12, at midnight ( Saskatchewan time ).