Scene Dynamics

Adding complexity to your plot

Until now, we've viewed story and WOARO in a linear path:

A character wants something, but something stands in their way. They take action, get responses, and eventually get what they want or don't. It's a straightforward journey from A to B.

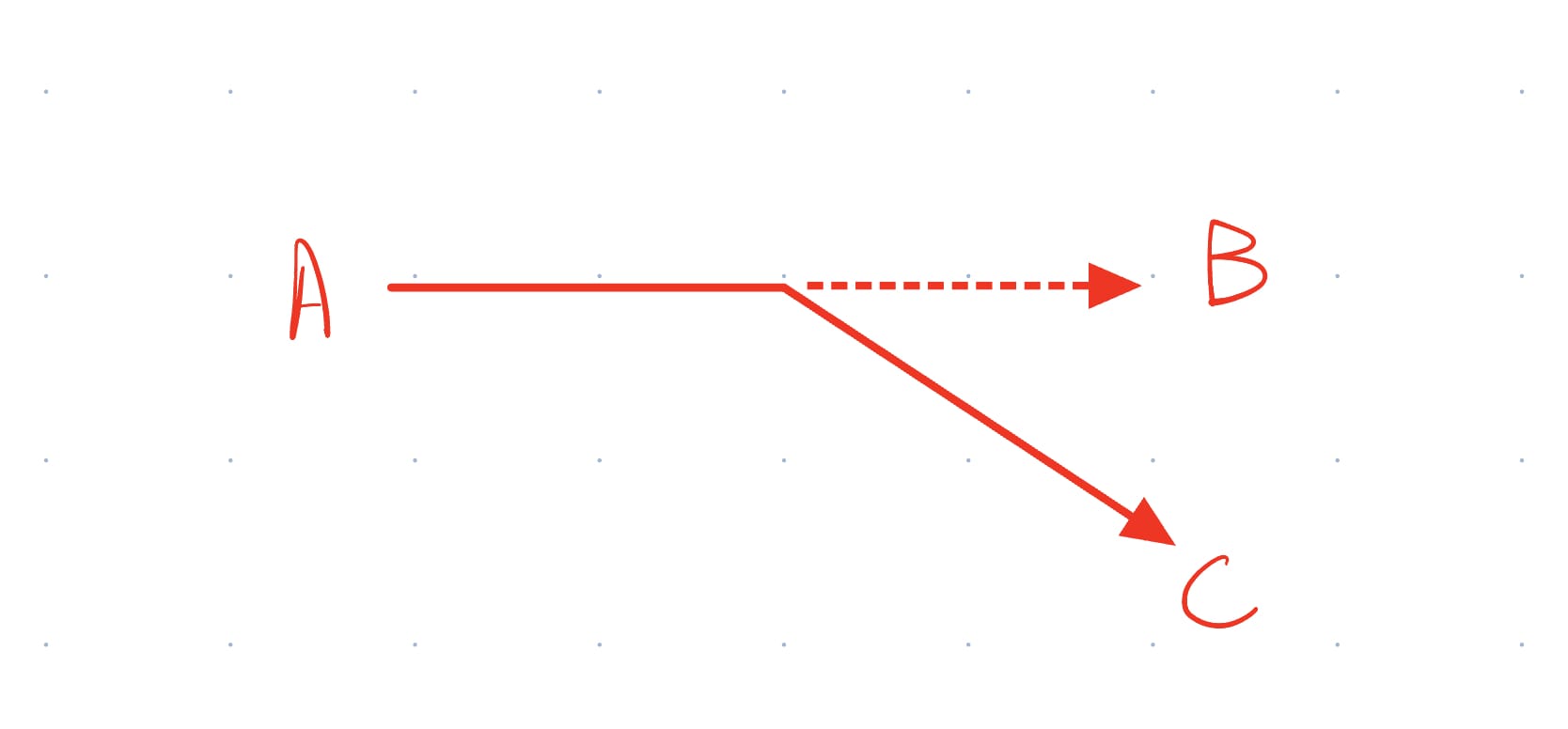

However, stories can be more complex, shifting or opening in unexpected ways. These shifts can be plot twists, new directions, or reveals that deepen the storytelling experience. What we believe is a simple path from A to B might suddenly veer towards C.

In this section, we'll explore tools like reversals, raising the stakes, and try/fail cycles. These techniques can help you craft more intricate and engaging narratives, full of surprising turns and rich storytelling moments.

Reversals

Reversals occur when the expected outcome of a story changes. We think our hero will lose but discovers the answer, or they've almost won and suddenly loses.

Reversals can occur for a few reasons:

- Recognition

- Hidden actions

- Unexpected responses

- Unexpected outcomes

- More than one outcome⠀

Let’s look at each of them.

Recognition

Recognition is when a character comes to a sudden realization or understanding.

An example is The Sixth Sense, in which Bruce Willis discovers that he is a ghost and didn't survive the encounter with the patient at the start of the story.

In terms of WOARO, recognition often serves as an unexpected outcome. The character's want might be to solve a mystery, their actions move toward solving it, but the outcome is an unexpected recognition that shifts their understanding of their situation or identity.

Aristotle believed there was a hierarchy of recognition, moving from least to most artistic:

- Signs (scars, tokens, etc.)

- Being told (I am the killer.)

- Forgotten memories.

- The process of reasoning through the facts and actions of the story.

The most impactful recognitions often fall into the last category, where characters (and audiences) piece together clues to reach a startling conclusion. This type of recognition can create powerful reversals, deepening the story and engaging the audience on multiple levels.

Recognition can also lead to new wants and obstacles, potentially spawning entire new storylines or dramatically altering existing ones.

Hidden actions

Another powerful type of reversal comes from hidden actions. While in most scenes and stories we understand who initially controls the action, hidden actions add an element of surprise and complexity.

Typically, one character wants something and takes visible actions to achieve it. However, hidden actions occur when a character has an ulterior motive and is waiting for the right moment to act upon it. These can create dramatic reversals, shifting the story in unexpected directions.

Hidden actions can take several forms:

- A False Action: their major action seems to be one thing when it is something else.

- A Withheld Action: kept in reserve, to be revealed later.

- A Sleeper Action: They seem not to pay attention to a character—until they do.

- A "Letting Out Line" Action: letting the other characters tire themselves out.

- A "Treading Water" Action: conserving energy, waiting to heal or recharge.⠀

Each of these creates potential for reversals because one character works against another at an unexpected moment. The reveal of a hidden action can dramatically shift the power dynamics of a scene or story, creating those surprising turns that engage audiences.

Hidden actions are also a powerful reminder that every character in your story has their own wants, obstacles, and actions. While the main character's journey might be at the forefront, other characters are pursuing their own agendas, sometimes in ways that aren't immediately apparent.

To effectively use hidden actions:

- Lay subtle groundwork for the reveal, ensuring it feels surprising yet inevitable in hindsight.

- Consider the motivations driving the hidden action. What does the character hope to achieve?

- Think about the timing of the reveal for maximum dramatic impact.

- Use hidden actions to add depth to your characters and complexity to your plot.

Unexpected responses

A story can often shift when a character's response differs from what is expected. This shift is different from a character with a hidden intention and action.

For example, a character could always say yes but suddenly say no. Or someone who's fought for a long time and suddenly gives up.

These moments reveal characters who dig deep within themselves and ask Who am I? and aren't happy with what they see.

On the other hand, some stories—often tragedies—have characters that face this question and accept their dark side, leading to further problems. Shakespeare was the king of this.

Unexpected responses and stimuli can also lead to moments of recognition. A character who responds unexpectedly could trigger a moment of a fresh understanding of the situation within another character.

Either way, the result is the same—a moment that changes the line of action and sometimes shifts who controls the action from one character to another.

Unexpected outcomes

In storytelling, the ideal outcome often aligns with what the audience wants - typically for the hero to succeed. However, the key to engaging storytelling is not whether the hero wins, but how unexpectedly that victory (or defeat) comes about.

While audiences might anticipate a certain result, skilled storytellers can surprise us with various types of outcomes, each adding depth and complexity to the narrative:

- Last-Minute Victory: The most common unexpected outcome is when the hero seems destined to fail until the very last moment. In Michael Clayton, the titular character appears to have lost against the corrupt corporation until he reveals he's been recording their confession, turning defeat into victory in the final minutes.

- Mixed Outcomes (Success/Fail): The hero achieves their primary goal but at a significant cost. The Empire Strikes Back is a prime example: Luke survives his confrontation with Vader and escapes, but loses his hand, learns a terrible truth about his father, and fails to save Han Solo.

- Unexpected Defeat: Sometimes, the hero loses against all expectations. In Avengers: Infinity War, Thanos succeeds in his plan to eliminate half of all life in the universe, despite the heroes' best efforts.

- Fail/Fail: Characters don't get what they want and suffer additional losses. In No Country for Old Men, Llewelyn fails to keep the money and loses his life, while Sheriff Bell fails to save Llewelyn or catch the killer, leading to his disillusioned retirement.

- Success/Success: Characters get what they want plus unexpected benefits. In Back to the Future, Marty ensures his parents fall in love and returns to a much-improved present.

The key to these outcomes is that they play out in ways neither the characters nor the audience fully anticipate. This unpredictability creates reversals, subverts expectations, and opens new story possibilities.

The goal isn't just to determine if the hero wins or loses, but to make the journey to that outcome as unpredictable and engaging as possible.

More than one outcome

As mentioned earlier, we've discussed story as a single unit of action called WOARO. When WOARO ends, so does the story.

However, I’ve also said in the past that WOARO can shape any story size, from a scene to a sequence, act, story, or series.

This approach allows us to nest stories inside other stories or create episodic connections. Once we understand WOARO's basic structure, we can play with its form.

One of those forms, of course, is reversals. A story seems resolved, only for a new storyline to burst onto the scene. You can also use it to dig deeper into a character's story.

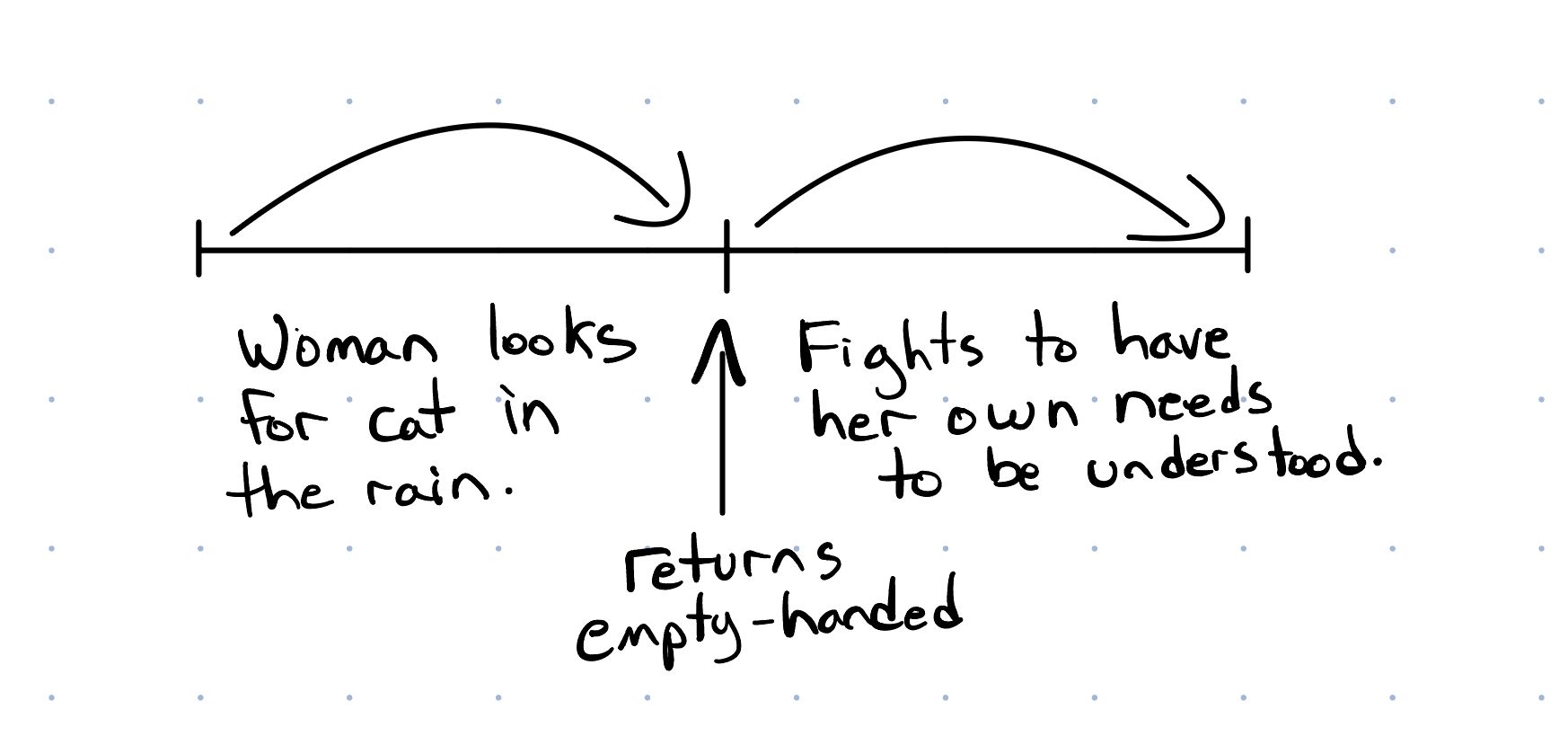

Ernest Hemingway often used this strategy in his short stories:

- In "A Cat in the Rain," the initial WOARO appears to be a woman looking for a cat in a rainstorm. However, when she returns empty-handed, a new WOARO emerges, revealing her deeper desires for a home and possibly a child.

- "A Clean Well-Lighted Place" begins with two bartenders kicking an old man out of their bar. This initial WOARO then shifts, following the older bartender into his own more profound existential struggle.

Both stories are structured to pivot at the midpoint, effectively creating two interconnected WOAROs within a single narrative. This technique allows Hemingway to explore deeper themes and character motivations beyond the surface-level plot.

Other examples are:

- Parasite (2019): The Kim family's initial WOARO is to infiltrate the Park family's household for employment. Once achieved, new WOAROs emerge involving the housekeeper and the hidden bunker, dramatically shifting the story's direction.

- Knives Out (2019): The film begins with the WOARO of solving Harlan Thrombey's death. Midway through, there’s a major shift as we learn how Harlan actually died. This revelation then pivots the story to Marta's WOARO of trying to covering up what she believes to be her mistake, before it shifts again to reveal the culprit.

- Persona (1966): The film begins with a WOARO centered on Nurse Alma caring for Elisabet Vogler, a mute actress. Midway through, the film dramatically shifts both in narrative and form. The story transforms into an exploration of identity merging, with the lines between Alma and Elisabet blurring. This shift is marked by a striking scene where the film itself appears to break down visually. The initial WOARO dissolves, replaced by a more abstract examination of personality and performance.

Raising the Stakes

Raising the stakes is another powerful technique for altering your story's trajectory and keeping it dynamic.

Introducing new challenges or intensifying existing conflicts forces characters onto unexpected paths and opens up fresh narrative possibilities.

We raise the stakes by:

- Complicating existing obstacles: This requires the protagonist to solve their problem in a more complex or specific way. For example, they might need to defuse a bomb, but now they must do it without cutting any wires.

- Introducing new obstacles: This adds additional problems the protagonist must solve alongside their main goal. Often, they've feared or worried about these issues becoming future problems or separate issues that now impact the main storyline.

- Threatening what the hero values: This could be loved ones, their reputation, their moral code, or anything else that matters deeply to them.

- Creating more unpleasant potential outcomes: These are often based on the hero's deepest fears and worries, bringing them closer to reality.

The key to effectively raising stakes is identifying what the hero cares about, worries about, or fears. These points of vulnerability can be used to complicate their journey and deepen the narrative.

For example:

- In an action story, the initial goal might be to defuse a bomb. Raising the stakes could involve revealing that the hero's family is in the blast radius (threatening what they care about) or that the bomb contains a deadly virus (creating a more unpleasant potential outcome).

- In a romance, the initial goal might be to win someone's affection. Stakes could be raised by introducing a rival (new obstacle), risking the protagonist's lifelong friendship (threatening what they care about), or potentially losing a once-in-a-lifetime career opportunity (unpleasant outcome).

Remember, raising stakes isn't just about making things harder for your hero but also about deepening the audience's emotional investment in the outcome. Each raised stake should make the audience more eager to see how the hero will overcome these intensified challenges.

By skillfully escalating stakes, you create opportunities for unexpected outcomes or reveal hidden actions, leading to powerful reversals that can dramatically shift your story's direction. This keeps your narrative fresh and your audience engaged, continually surprising and captivating them throughout the journey.

Try/Fail Cycles

In a previous section, we explored try/fail cycles as a fundamental storytelling tool. Here, we'll consider how these cycles interact with reversals and raise stakes to create more dynamic narratives.

Remember, try/fail cycles involve your character attempting to solve a problem, failing, and trying again. These cycles can be powerful tools for implementing reversals and raising stakes:

- Reversals through Try/Fail: A character might experience a reversal when a "yes, but" outcome leads to an unexpected new obstacle or when a "no, and" failure reveals hidden information.

- Raising Stakes with Try/Fail: Each failure in a try/fail cycle can naturally raise the stakes. As the character exhausts options, the consequences of ultimate failure become more severe.

- Complex Outcomes: Try/fail cycles can lead to the complex outcomes we discussed (success/fail, fail/fail, success/success) by combining different results within a single cycle.

By strategically using try/fail cycles with reversals and raised stakes, you can create a more unpredictable and engaging narrative structure.

Final Thoughts

As you can see, the interplay of reversals, raised stakes, and try/fail cycles is at the heart of dynamic storytelling.

Stories rarely travel in one direction and effectively using WOARO to create plot twists, reversals, and revelations can help open and deepen your narratives.

Remember these key points as you craft your stories:

- Reversals keep your story unpredictable and engaging.

- Raised stakes deepen the audience's emotional investment.

- Try/fail cycles provide structure and opportunities for reversals and raised stakes.

By implementing these tools thoughtfully, you can craft engaging stories that resonate deeply with your audience.